“The truest thing you know is what is getting your attention the most. Change who is around you and change the information feed coming to you such that what is most true and meaningful is what you're getting reminded of the most.”

– Daniel Schmachtenberger

In my previous post on compassionate critique (see below):

Compassionate Critique

Thank you for continuing this journey into negotiating reality and tuning commonsense! Please note that each post here is meant to valuable on its own, while also build on one another. With that, you are most welcome to read this or any other post at your leisure to see if you might find some interest here.

I introduced the idea of a "bubble." By "bubble," I mean what a person can and does perceive about reality. We all live within our own bubbles, but we often fail to recognize this or understand its implications for how we navigate the world with others.

The purpose of this post is to explore this concept in greater depth. What is a bubble? How can we navigate each other's bubbles? What does this mean for foundational concepts like being "unbiased" and "objective" as used in the sciences? If these questions intrigue you, read on!

What Makes Up a Person’s "Bubble"?

There are many ways to answer this question, drawing from diverse wisdom traditions. The way we analyze our bubbles is crucial because it shapes how we see and perceive the world. I will explore this in more detail in a future episode that will be titled Beings Adapt.

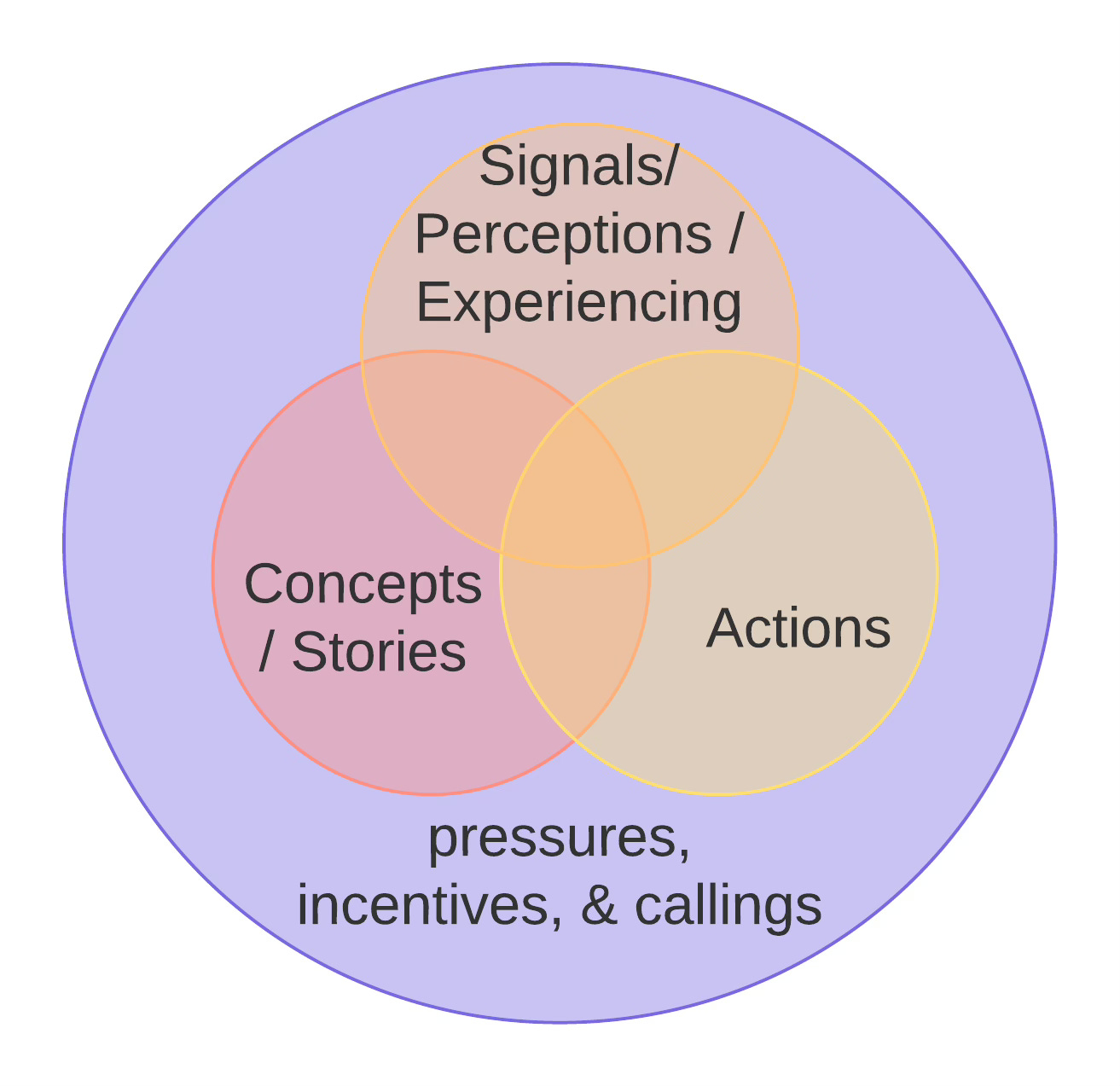

For now, consider the visual model above. While no model fully represents reality, models serve as tools for communication. I created this model to support practicing compassion toward oneself and others and, in particular, to guide the sort of questions to ask for understanding oneself and other’s bubble. This model has limitations—if your goal is to fully understand human experience without mediation through language or representations, this model will not help.

In keeping with the compassionate critique approach of matching, this model should only be used in appropriate contexts—specifically, when trying to cultivate compassion for oneself or others.

With that caveat, let’s delve into some key questions that help flesh out one’s own and others’ bubbles:

What signals and perceptions do I/they experience or have the capacity to experience?

What concepts or stories do I/they use to make sense of and explain life events?

What actions do I/they believe are available to me/them?

What pressures, incentives, or cultural influences shape my/their perceptions and decisions?

The answers to these questions define a person’s bubble.

Why Use the Term "Bubble"?

The term "bubble" is commonly used to describe how people perceive reality in their own distinct ways. When we say someone is "living in a bubble," it aligns with the concept I am discussing here.

Additionally, a bubble’s physical properties—how it moves, changes, reflects, merges, and separates—mirror how our perceptions shift over time. I assume that human bubbles are highly dynamic and constantly evolving. Picture a floating bubble in the air, adjusting and transforming as it moves—that’s how our perspectives shift.

For example, people effortlessly switch between focusing on the past, present, and future, sometimes even cultivating a timeless awareness through rigorous training. A bubble can expand or contract depending on focus. A person “in the zone” at work might have a narrowly concentrated bubble, while someone practicing mindfulness may cultivate an expansive perspective and thus very large bubble.

Humans are constantly adapting, and our capacity to experience a vast range of perspectives is remarkable. The term "bubble" acknowledges both the beauty and dynamism of human perception and experience.

Example: Physician-Patient Interaction

In my previous post on compassionate critique, I used physician-patient interactions as an example. This scenario is familiar to most people and illustrates the concept well.

Imagine a physician and a patient discussing cardiovascular disease management, considering options like diet and exercise. Both individuals bring their own bubbles into the conversation.

The Physician’s Bubble

Physicians work under immense pressure, often with limited time (e.g., 15-minute appointments) to listen, assess, and make critical decisions. They are incentivized to move efficiently to maximize billable hours. Many enter the field out of a deep sense of calling, yet they struggle with systemic constraints.

Physicians rely on evidence-based recommendations for screening, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Their available actions are dictated by the healthcare system, such as prescribing medications, recommending diet programs, or suggesting medical devices. Their training also emphasizes specialization, meaning they are attuned to some signals while potentially overlooking others. For instance, a gastroenterologist is more likely to detect gut-related symptoms, while an oncologist may excel at recognizing cancer-related signs. Geographic context also matters—For example, East Coast physicians are generally better at diagnosing Lyme disease compared to those on the West Coast, where the disease is less prevalent.

The Patient’s Bubble

Patients bring their own pressures, incentives, and values into the interaction. A patient may experience cultural or familial expectations around food, incentives like the pleasure of drinking alcohol, or personal commitments to holistic health approaches. They may trust information sources that are not traditional institutions that emphasize the risks of processed foods or pharmaceuticals.

A patient’s bubble influences the signals they pay attention to. Someone inclined toward homeopathy might place greater importance on bodily sensations than on lab results, for example. Understanding these differing bubbles is essential for creating shared understanding and making informed decisions.

Applying a compassionate critique approach (described in a sister post), would result in these bubbles being considered in the physician-patient interactions. In practice, this means the physician and patient would work to understand each other’s bubbles before negotiating treatment options. For instance, a patient might advocate for alternative medicine, while the physician offers insights into when such approaches might be effective and also potential skepticism they may have, without coercing the patient into agreeing with them. The goal is to cultivate a shared reality and a mutually agreeable plan, with an ongoing commitment to learning and adjusting over time.

Why This Matters

Understanding bubbles is not about striving for "objectivity" or being "unbiased." The premise here is that humans are not omniscient. Instead of labeling people as biased or irrational, we acknowledge that everyone operates rationally within the constraints of their perceptual range—their bubble. This builds on Herbert Simon’s concept of "Bounded Rationality," which underpins behavioral economics. Bounded rationality asserts that humans make rational choices based on their available information and cognitive limitations (i.e., their bubbles).

By incorporating bubbles into discussions, we shift away from moralizing judgments and toward constructive engagement. For instance, someone may live in a bubble that prioritizes survival but inadvertently harms others. Alternatively, someone may have an overly broad focus and lack practical knowledge of their immediate environment, thus creating harm through neglect or ignorance. Others may have limited emotional granularity, perceiving only a few emotions (e.g., happy or angry), which might make their decisions less reliable. Still others may experience learned helplessness due to a restricted perception of available actions, while others suffer from choice paralysis due to overwhelming options.

In each of these options, understanding someone’s bubble allows for people to connect with one another as humans, in all of our beauty, frailty, and complexity. In that space of shared recognition, one can find new options that are often not possible when alternatives, such as judging and moralizing actions occurs (there is, indeed, a time and place even for that, particularly when a person is consciously acting in bad faith and bad will, but, those times are far more rare and should be engaged only when there is clear evidence to demonstrate a person is acting in baith faith or bad will, see this post for more details on this ideas and, I’d be happy to go more into depth on this in a future post, if you’d like. Just let me know!).

Recognizing these patterns helps us develop skills to take responsibility for our bubbles and navigate them effectively. Rather than seeking to be "unbiased," our goal should be to develop the skill of being able to both “fuse” to one’s experiences and also de-fuse from one’s experience. By fuse, I mean a practice of seeking to be fully present and some might say “mindful” of a moment. To fully feel, live, and experience, as holistically as possible. There are times and places when full fusion with being alive, in love, and aware is it all is valuable and important. With this, one embraces and lives into one’s bubble as full, whole, one experience. In contrast, there are also times when one may seek to defuse from one’s life and experiences. This experience, which is more close to what the ideal of being “unbiased” or “objective” might be, is valuable to help establish a certain degree of non-attachment to one’s life. It’s being able to live into a continued separation from one experience, as exemplified by this set of phrases, all moving towards increased de-fusion. I am sad. I am having the experience of sadness. I am having the experience of sadness in this moment. I’m having the experience of sadness in this moment in this context. Eric is having an experience of sadness in this moment, in this context. Etc. Truly feeling and being able to “see” from this defused vantage can be extremely valuable (and is a practice that is taught in a range of wisdom traditions, such as Buddhism).

Flowing through fusion (with one’s bubble) and de-fusion (expanding one’s bubble) provides a pathway for honoring the wisdom of being “objective” while also recognize that there are times and places when it is also valuable to be fully enmeshed and living in reality. This “bubble” work creates a way of thinking about that that is not currently available in traditional “objective” scientific discourse.

And, with this, it provides a structure for negotiating shared understandings of reality and defining what "good" looks like collaboratively. This allows us to co-create a desired future state through informed, compassionate discourse.