Compassionate Critique

An updated approach to classical academic critique that was based more purely on Socratic Dialogue alone

Thank you for your interest in negotiating reality and getting into the weeds with me on process!

This current post explains “compassionate critique” approach developed by my colleague Elizabeth Eikey and me. It will serve as a guide for moderating this space.

What is compassionate critique?

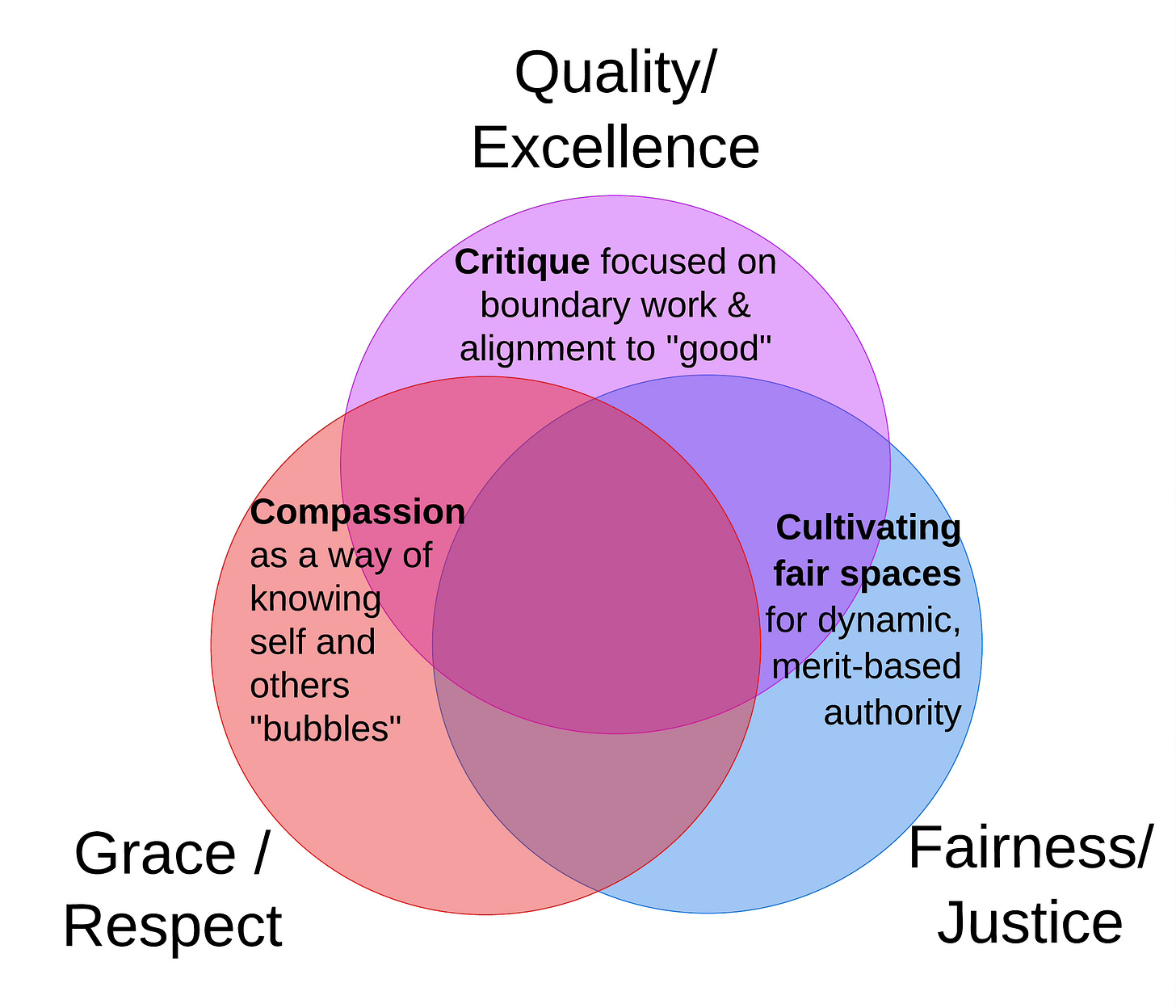

The goal of compassionate critique is to foster dialogue between two or more people that cultivates:

A shared understanding of reality.

A shared notion of what is “good” or desirable—such as defining a goal—and evaluating options to achieve that goal that are realistic.

The three core elements are:

Compassion, which involves practices in understanding oneself and others as individuals with unique perspectives or “bubbles” of reality (for more information about “bubbles” go here).

Fair engagement, which involves practices in creating a group dynamic that recognizes and respects expertise relevant to the topic, rather than relying on historical precedent to confer status.

Focused critique, which involves practices in defining the boundaries of a concept’s relevance and usefulness, to enable a group to tune into when, where, and for whom ideas/solutions/tools are appropriate and valuable.

A helpful analogy: Tape measure vs. GPS

Traditional critique is like developing and using a tape measure—focused on precise definitions and objective measurements. While useful, it’s insufficient when used alone for navigating complex realities.

Compassionate critique, by contrast, functions more like GPS navigation. It relies on shared definitions that can be created using traditional critique and adds additional referents to support people in navigating through reality to achieve a shared goal.

To unpack this a bit…

Traditional critique is particularly valuable for clarifying concepts to define what an object is that everyone can then agree upon.

For example, a Socratic dialogue would work something like this:

Teacher: What is a square?

Student: A shape with four sides.

Teacher: Are there other shapes with four sides?

Student: Yes, a door or rectangle.

Teacher: What then makes a square different from a rectangle?

Student: A square, then, is a shape with four equal sides.

Traditional critique emphasizes this form of careful questioning to specify objects and objective measurement(s). Returning to our square example, this method would support developing statements like: “I will judge if something is a square if I can observe four sides that are equal in length.”

With this definition of a square defined, an objective measure, such as a tape measure, could be created to enable anyone to measure the length of a four-sided object to determine if that object is a square. If the four side are equal then, by this shared definition, it is a square, which can be verified by others.

This basic logic is valuable and powerful and one important starting point for creating a shared understanding of reality. It is also insufficient when navigating complex realities, particularly with potential differing perspectives, status differentials between perspectives, and when differing goals/intentions are present.

Compassionate Critique takes advantage of traditional critique while adding layers that account for the fact that humans are doing the work. Specifically, compassionate critique adds compassionate contemplation to support perspective-taking, active co-creation of a shared model to guide dynamically conferring status within a group, and active co-creation of goals and intentions to tune future actions and decisions towards these desired states.

Returning to the GPS analogy,

multiple perspectives are akin to the need for multiple GPS satellites. Participants bring diverse expertise, histories, and knowledge that each contribute towards a richer understanding of reality and its complexities. Practices in compassion, both for self and others, are used to help all individuals understand and clarify their perspectives and the perspectives of others, with the goal of seeking non-moralizing, non-judgmental, compassionate understanding of one another.

A co-created model of status is akin to the 3D Model/Map of coordinates that GPS relies upon to link its observations to the real-world. In compassionate critique this translates to active negotiation and discussion of the social norms and rules of engagement that are used within a group to create a shared set of customs that dynamically confer status to whoever has the best grasp of reality relevant to the discussion at hand.

Co-created goals are akin to the desired location one is trying to navigate to via GPS. In compassionate critique, this translates to a group actively co-creating a shared understanding of different possible goals and intentions that different individuals or groups may be striving for. These goals and intentions can then be used to help evaluate alternative ideas and options, within focal areas of interest, to help the group attune to actions that are deemed realistic for advancing shared intentions (as well as recognition when groups may end up with differing intentions and goals or be focusing on different areas of interest).

A real-world example: Patient-physician interactions

Imagine a physician working with a patient with cardiovascular disease.

The traditional interaction, which grows out of the traditional critique approach, involves a physician asking probing questions, much like a Socratic dialogue between a teacher and student. The focus of this interaction is to have the physician link what a patient says and is experiencing to what the physician knows about various diseases. Through this dialogue, a physician develops recommendations on actions to take to help the patient. For example, evidence-based guidelines suggest that diet, exercise, and a range of medications, such as statins, could be considered when trying to help a patient control cardiovascular disease. The physician will ask questions geared that will enable them to make good recommendations for their patient.

In a compassionate critique approach, the physician and patient would work together, to consider the patient’s unique circumstances—cultural norms, food access, preferences, and personal goals—to co-create a plan. This will be done with key shifts in the practice including:

Compassionate Understanding: Both physician and patient explore their “bubbles”—the factors shaping their perspectives and decisions, to allow the wisdom from both the patient and the physician to be considered when deciding in the right next steps.

Fair Dialogue: Both the patient and physician would be invited to both acknowledge the knowledge, wisdom, and expertise each person is bringing into the room. With that, the patient and physician can create a shared understanding on when to defer to one another. For example, when decisions about differential diagnosis between different diseases is occurring, the physician is more likely to have a more complete “bubble”/grasp of reality and thus, would likely be deferred to. When decisions are focused more on deciding which actions are viable, such as different dietary choices, then the physician would defer to the knowledge, experiences, and wisdom of the patient.

Moving towards consent on an action plan for achieving a mutually agreed upon goal: The physician and patient would work together to explore their options, discuss the pros and cons of various options and, ultimately, come to a plan where both the physician and patient can consent to an action plan that they both see as acceptable for achieving a shared goal.

When is compassionate critique needed?

The more complex a situation, the more likely compassionate critique is needed.

To illustrate this point, let’s return to our patient-physician interaction. The goal of this interaction could be stated as such: to select the “right” type of support for each patient, at the right time, in the right context, that will produce the desired result. Doing this well is impacted by the inherent complexity of the phenomenon. When a physician is dealing with relatively simple issues, like blood transfusions, where all that is needed is knowledge of blood type, then this is very easy. Similarly, when the physician is making decisions about acute diseases, such as cold, flus, infections, and the like, the cause is often simple (i.e., the patient likely has a bacterial infection) and thus, the solutions can be simple (i.e., prescribe an antibiotic).

These sorts of simple scenarios are where the classic Socratic dialogue can really shine! For these types simple phenomena, the physician does hold much of the key knowledge needed to do differential diagnosis and, thus, through careful probing questions, can come to the right type of care, such as prescribing antibiotics.

In contrast, trying to support individuals in eating more healthfully and to engage in exercise is far more complex. The general recommendation to “eat healthy” might seem simple, but there’s a wide range of complexities that need to be factored in. For example, individual differences, such as food preferences, cultural practices, food access, time of day, learning history, etc, that influence what a person eats need to be considered (people are different). Not only that, but what, when, and how a person eats is influenced by a wide range of factors, such as their physiology, their social groups, and norms around eating, and the environments they live in and the degree to which they are conducive of healthy eating or not (Context matters). Finally, all these factors about individuals, groups, and their contexts, are changing … with this, what might “work” for a patient at one time, might stop working or need to evolve (things change).

For complex issues such as this, a classic Socratic dialogue is insufficient. For something like diet, the wisdom of the patient, including their own knowledge of their histories, food preferences, cultural norms, home environment, communities, food access, etc, need to be factored in. This is where compassionate critique comes into play and its use of compassion, cultivating fair spaces, and critique geared towards matchmaking can be useful.

How will compassionate critique be used to help negotiate reality?

As this is open to the public, anyone can read any of these posts at any time, in any order they want.

With that said, if you are interested in going deeper and really negotiating with me and others, then I’d invite you to commit to practicing compassion for yourself and others before critiquing.

Whenever you engage here, the first step I recommend is compassionate listening. With this, the goal is to come to an understanding of your and other’s bubbles/perspective on reality that is compassionate to both you and others. Critically, you do not need to agree with someone else’s bubble…instead, the goal is to understand, with compassion, how and why a person may have gotten to the conclusions they may have come to.

This can be quite hard for some people and, if you are finding it hard, feel free to look into this worksheet we assigned our students (see related post on the history of this approach) as a weekly compassionate reflection for some inspiration on practices.

I would also strongly recommend the two books below, Practicing Compassion and a Fearless Heart, for a more detailed instructions on how to practice compassion. In my experience teaching students, the Practicing Compassion exercises are particularly valuable when you are trying to understand someone you deeply disagree with while remaining compassionate for yourself and your perspective.

Second, critique but with a focus on defining when, where, and for whom something may be true/appropriate/aligned.

Once you’ve used compassion to understand where someone (such as me, Eric, the one writing this write now, note, I have sister posts describing my lineage, my research background, and my spiritual development, in case you are interested) is coming from, I invite you to start to explore critique. Within critique, you can, of course, continue to use classic Socratic questioning, particularly if you suspect a term is being used and understood in a way that you do not understand or agree with. In addition to this, I’d suggest you add questions related to matching. Example questions include:

Who are the key people and perspectives that are impacted by this?

How would/should they respond? What would they see that might be missing? What might they appreciate?

If you are one of those people impacted by these ideas directly, what experiences or expertise do you have that the person who offered this idea might not now about? How could you compassionately communicate this to nurture a shared sense of reality?

What power differentials may be coming into play here? What, if anything, could be done about this to help the group get a better grasp on reality as it is?

When, where, and for whom would this idea be particularly valuable and appropriate? Why?

When, where, and for whom would this idea be problematic? Why?

What are the similarities and differences between this idea and other ideas?

What assumptions are now visible to you that you were making about something that you had not realized previously? Why do those assumptions matter, if at all?

Are there ways to combine, synthesize, or connect these different ideas to make them stronger in some way? If so, how?

Third, monitor for fairness of the space and actively negotiate the norms and rules to ensure status flows dynamically to whoever as the best grasp of reality in relation to the topic at hand.

The last step involving keeping track of any possible unfairness in discussions. By unfair, I’m referring to a person being given status based purely on historical precendent, not their grasp of reality in relation to others in the group and the topic at hand. Things to look out for here include issues like. if you or anyone else might feel pressured or coerced in some way to consent or agree to an idea… or maybe you do not feel like you could speak…or, maybe you notice someone else that is not engaging as much or as often as others. If you ever notice this, actively pause the conversation to focus on the cultural norms and rules of engagement and re-negotiate them together. For example, you can do this through the following sorts of activities.

Invite everyone to feel capable in shifting the conversation towards discussing the rules of engagement, norms, defaults, or otherwise about HOW the conversation is taking place. To support this, in this space, I ask you to ask yourself these sorts of questions:

Who has the right to speak and when? Why?

Who has the right to interrupt? Why?

Who has the right to express emotions? Why?

Who as the right to claim authority? Why?

What type of person is favored in the current rules of engagement? Who might be experiencing marginalizing in this current space? Why?

Discuss observations within the group, with a particular focus on using compassion to understand one another’s perspective and, in particular, to try and understand the ways in which historical precedence may be coming into play. As you do this, think compassionately on why that historical precedent came into being? What was it serving? What are the unintended consequences of the precedent? Is there insight from the past that is still relevant today? If not, how should the rules change?

Engage in active negotiation on explicitly changing the rules of engagement, norms, etc, to ensure the space is conferring status to whomever the group dynamically views as having the best grasp on reality for a given part of a discussion. For example, this could involve the group discussing rules on when, where, and how people can interrupt, how time is managed and spaced out, etc.

Commit to continually seek to do better, while also giving the benefit of the doubt to one another, given the spaces shared commitment to good faith and good will interactions.

If you’d like to see it, here’s the worksheet we gave for our students to use in a group discussion space that pulls all these ideas together.

Next steps

This overview captures the essence of compassionate critique. If you’re ready to engage with these principles, let me know. If you have questions or suggestions, feel free to share. Together, we can refine this approach and create a fair, no-pressure space for meaningful dialogue as we negotiate reality together.

For those interested in deeper insights, I’ve developed some optional write-ups that you can go deeper on. In my view, all of these are just meant for those who want to go deeper. There are three posts that you might want to explore:

Check out this post

Then this post:

Check out this post entitled, “You are interacting with a zombie,” if you are struggling to navigate our current media and “attention economy” landscape (forthcoming).

Bibliography

Why we need a small data paradigm