Throughout my life, I have been blessed with the gift of music—surrounding me, supporting me, flowing through me, and emerging as a guide, particularly when I least expected it. Music has always been my way of staying connected to and guided by sacred love even—perhaps especially—when my rational mind resisted it.

My Spiritual Roots as a Lutheran/Christian

The photo above is from my wedding with Andrea in 2010. It includes my parents (standing on either side of us; Andrea and I are in the center), my brothers, Garth and Peter, and their families (mostly on the left). Also present are my uncle, cousins, and their families/significant others. Since this photo was taken, our family has grown, including the addition of our son, Elijah.

A few family members are absent from this picture, including my grandparents, who had all passed away before Andrea and I got married. My dad’s brother and his wife had also passed away by this time. My aunt (married to my uncle standing next to my mom) and my mom’s sister, who attended the wedding but wasn’t in this photo, are also missing. Honestly, I’m not sure why she wasn’t included, and I feel a bit guilty not seeing her there. She was struck with polio as a child and moves with difficulty, though thankfully, she’s still going strong at 85! Some of my cousins are also not represented here.

These were the people who shaped my childhood, offering love, support, and guidance. As an aside, this picture was taken by the Hudson River at the boat club where my dad was a member. Every summer, we took an annual sailing trip down the Hudson River, around Manhattan, and into Long Island Sound—a cherished tradition.

Everyone in my family, from my grandparents to my parents, aunts, and uncles, was raised in the Lutheran Church, though not all remain active members. I was baptized at Redeemer Lutheran Church in Kingston, NY, where I attended Sunday School, participated in church camps, and completed my first communion and confirmation classes.

In the church (like so many others), is very likely where I first started to sing and sing regularly. When in service, as part of a youth group singing, etc. I also always loved the music, particularly the choir singing, which my mom and dad were both a part of.

My parents were deeply involved in the church, and my mom remains active there today. Their closest friends—many of whom became my honorary “aunts and uncles”—were either members of Redeemer Lutheran or the boat club. These relationships remain strong to this day.

In addition to her lifelong involvement, my mom is a Deacon at Redeemer, an ordained clergy member dedicated to serving both the church and the Kingston community. Growing up in a Christian household, I was surrounded by family who were devout in their faith and committed to living out the good work of Jesus.

Embracing Atheism during high school, college, and grad school

There was much I have always appreciated about the Church: the sense of community, the space for moral and spiritual conversations, the structured support for people coming together in service to one another, and, of course, the music. However, as is common in many spiritual journeys, my high school and college years were marked by an active rejection of the Church and its teachings.

Looking back, I now have a clearer understanding of what triggered this shift (which I’ll return to in later posts as I do have a recalibrated perspective on all of these that does not negate my early experiences, but also does not let them fully define my relationship to Christianity and my ancestry), but at the time, several key issues drove me away:

Unbelievable Teachings – Many of the stories and depictions of God the Father seemed to me like a reimagining of Zeus—an all-powerful patriarchal figure. Others have likened these portrayals to worshiping the “Flying Spaghetti Monster,” and I found that comparison fitting.

Unsatisfying Answers to My Questions – When I raised concerns, the responses often boiled down to variations of "believe your beliefs and doubt your doubts" or simply "have faith in Jesus." To me, this was deeply unsettling. If something were truly true, I felt it should be able to withstand skepticism and scrutiny—and, in fact, become stronger through challenge.

Historical Hypocrisy – I had no particular issue with the teachings of Jesus himself, but I was struck by the stark contrast between those teachings and the atrocities committed by the Church, particularly the Catholic Church, including:

St. Augustine’s concept of original sin and its far-reaching consequences.

The evolution of the Roman Catholic Church into a human-made institution wielding immense power, often in harmful ways.

The many so-called holy wars waged in Jesus’ name—wars that seemed entirely antithetical to his teachings.

The use of Biblical teachings to justify atrocities such as slavery and the genocide of Indigenous Peoples in the United States.

The apparent confident ignorance and emotional blindness I observed, particularly among those dedicated to Evangelism—who often sought to spread the "Good Word" through persuasion, coercion, and, at times, harm.

Amid these reflections, I immersed myself in the writings of the “Four Horsemen of Atheism,” such as Richard Dawkins. Their arguments resonated with me, leading me to conclude that atheism was the only logical choice—the only one that truly aligned with the evidence.

This led me, at some point, to reject even being able to sing in the church as it felt like I was lying.

With that, I am so grateful that I had music in my life to anchor me to the sacred, particularly when I didn’t know it was serving me that way.

Feeding My Soul Through Music – My High School Years

While my rational mind led me to atheism, my heart longed for beauty and transcendence. To this day, I often say that engaging in music is how I feed my soul (which was ironic as I didn’t believe in a soul for quite some time).

In church, there was always music around me and so I was basically born singing.

In elementary school, I was fortunate to have a wonderful music teacher who nurtured my voice and encouraged my singing. At first, this largely involved secular songs. For instance, I can still sing the song I learned as a child that lists the Presidents of the United States—and in my musical memory, it still ends with George Bush. 😉 (I can also recall the Fifty Nifty United States song.)

My teacher also supported me in developing the confidence to sing solos. One of my early roles was playing “Ralf Ledwards” in This is Your Life, Santa Claus. Around the same time, I began trumpet lessons and later joined the middle school band.

High School: Deepening My Musical Involvement

In high school, my passion for music expanded. I was active in school plays and had a pivotal moment when I had to choose between joining The Pit as a trumpet player or stepping on stage as a singer and actor—I chose the latter. I also participated in the marching band (as did my brother, Peter, when we overlapped in high school) and sang as a tenor in the school choir.

Kingston High School had a strong music program that allowed me to flourish. Over time, I took on leadership roles, becoming an assistant conductor for the choir and one of the drum majors in the marching band. Whether singing, playing the trumpet, or conducting, I had the opportunity to engage with a wide repertoire of classical, jazz, and blues music—both secular and sacred.

Music as a Source of Meaning During My Atheist Years

During my atheist years, I felt more drawn to secular music because it seemed more honest to me. There were moments, particularly when attending Redeemer Lutheran Church, when I deliberately chose not to sing, feeling that doing so would be an act of performative faith—something I couldn’t bring myself to engage in.

Two pieces I had the privilege of conducting in high school stand out as particularly moving for me at that time:

"O Shenandoah" – Listen Here

A Welsh Lullaby – Listen Here

These songs deeply resonated with me at that time (and listening today, I still love them). They fed my soul in a way I couldn’t fully articulate at the time. I’m grateful that I never felt the need to justify my connection to them, because if I had, I might have talked myself out of pursuing music altogether.

I also had the privilege of conducting some incredible pieces in our marching band, including:

"The Great Gates of Kiev" from Pictures at an Exhibition – Listen Here

These were the kinds of pieces that drew me in most during high school.

Interestingly, the songs I remain most connected to today are the ones I had the privilege of conducting. While I loved singing—and still cherish opportunities to perform monumental works like Beethoven’s Ode to Joy (Ninth Symphony) with a professional orchestra and choir, or Handel’s Messiah (including the Hallelujah Chorus)—conducting brought me a unique sense of fulfillment.

For me, music was never just about lending my voice or playing the trumpet; it was about listening, learning, and helping bring out the best in a collective. Conducting gave me the chance to do just that, shaping the music in a way that resonated deeply with both myself and those around me.

Finding Community Through Music – My College Years

When I started college at SUNY Albany, I immediately joined the choir and quickly built a strong relationship with my mentor and teacher, David Griggs-Janower—known to most as DJ. Around the same time, I was fortunate to meet two fellow freshmen, Mike Kanevsky and David Pellingra (now Wolf-Pellingra). Together, we felt inspired to start an a cappella group, which we named The Earth Tones.

Growing Through Choral Music

As a member of the Chamber Chorus, led by DJ, I deepened my education and engagement with choral music. Over time, I grew into the role of DJ’s assistant conductor and, for a while, even pursued a major in music. However, at my father’s urging, I ultimately shifted my focus to psychology—though I still minored in music, education, and biology (and nearly in chemistry, but that’s another story more aligned with my research career).

Through my time in the choir, I not only learned and performed incredible music but also formed lasting connections. One of my fondest memories was our musical tour through Ireland. I was especially moved by the Irish people's deep love of music and the way they used song to bring people together.

The Earth Tones: A Musical Brotherhood

Within The Earth Tones, I found my closest friends—relationships that remain strong to this day. We did everything together, growing as musicians and as people. By the time we were seniors, the original founding members had become so close that twelve of us ended up living together in what was essentially a musical frat house.

With The Earth Tones, I learned how to be playful—how to laugh, joke, and perform in ways that brought joy to others through skits, songs, and shared experiences. It was also where I built deep personal connections, including with my college sweetheart, Jess. Through this group, I learned not only how to live and love but also how to care for one another—with a healthy dose of laughter and goofiness along the way.

Getting Unmoored – My Grad School Days

After college, I found myself in a difficult place. I had loved my time at SUNY Albany, but grad school felt completely different—I was disconnected, lost, and becoming someone who no longer felt like me.

Looking back, I now realize that this was the period when I fully let go of my dream of being a musician, and, by extension, became unmoored to the sacred.

My father had persuaded me to abandon that path, and instead, I resigned myself to becoming a psychological scientist (see Research Trajectory; and, as an aside, I’m grateful to my dad. I think he was right in his advice). This phase of my life marked the darkest days of my spiritual formation—not only did I embrace atheism, but I also drifted into nihilism and moral relativism, cloaked in the confident ignorance that came with training to be an “evidence-based scientist.”

During this time, I honed skills in precision of thought, representation, and language—yet I was utterly detached and unanchored from anything sacred. While I still engaged in music and enjoyed it, it was music stripped of any deeper spiritual connection. My involvement was purely secular, including performing with an a cappella group in New York City called City Blend and briefly serving as the lead singer for a band called The Odessa Steps. (as an aside, I loved being in both of these groups! No judgment here, just noting lack of spiritual fulfillment. They were all I likely could handle during this time of my life).

From 2002 to 2007, my years in New Jersey were when I felt most unmoored—adrift from the sacred and the beautiful. Unsurprisingly, this was also the period when I was at my lowest—depressed, confused, and fundamentally lost.

Feeling “O Magnum Mysterium” – My Year in Baltimore

As part of my Ph.D. in clinical health psychology, I was required to complete a one-year clinical internship, which I did at the VA Baltimore from 2007 to 2008. Though I was only in Baltimore for a short time, in hindsight, that year was a pivotal moment in my life—professionally, socially, and spiritually.

Professional Growth

During this time, I developed a meaningful friendship with Jaime Naifeh. It was with Jaime, in a bar of all places, that I had the conversation that ultimately helped me find purpose and direction in my research work (see Research Trajectory). That discussion shaped the path I would follow for years to come.

A Life-Changing Social Circle

Socially, Baltimore was transformative in ways I never expected. Through my supervisor at the VA, Clint McSherry, I was introduced to Andrea—who would later become my wife. Initially, we became roommates due to the high cost of living in the Bay Area and Andrea’s need to find a place that could accommodate her and her beloved dog, Cholla (I still miss Cholla—she passed away the year before our son was born). Two weeks after moving in together, Andrea and I started dating. From that moment on, we have lived together for the entire time we’ve known each other.

Baltimore also led me to Barb James through the Baltimore Choral Arts Society (more on that shortly). Barb worked in Maryland but owned a home in Palo Alto, right next to Stanford—where both Andrea and I became postdocs. As luck would have it, she was looking for someone to house-sit and care for her dog, Milo. She offered to rent her home to us at an incredibly affordable rate (if I remember correctly, $500/month), with the understanding that her son would live with us sometimes and that she would visit one week each month. The arrangement worked out beautifully, and we became close friends—so much so that Barb eventually officiated our wedding.

Spiritual Awakening Through Music

One of the most profound aspects of my time in Baltimore was my experience with the Baltimore Choral Arts Society (BCAS) under the direction of Tom Hall. I absolutely loved being part of BCAS. Through it, I had the chance to perform extraordinary music, including unforgettable collaborations with the Baltimore Symphony—such as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and Carmina Burana—under the renowned conductor Marin Alsop. I formed friendships and, for the first time in years, engaged in sacred music.

One moment, in particular, was transformative.

A Sacred Experience: Singing “O Magnum Mysterium”

We were performing a Christmas concert at the Baltimore Basilica, and I was part of the choir when we recorded an album (which you can find on Spotify, Apple Music, etc.). One of the pieces we performed was O Magnum Mysterium by Morten Lauridsen (listen here).

During a rehearsal, when it was just the choir—no audience, no distractions—the Basilica’s acoustics created this rich, resonant reverberation. As we sang, I lost all sense of I. There was no me—only we.

We were one.

In that moment, we weren’t just performing O Magnum Mysterium—we were bringing it into being. It was a sacred, transcendent moment, and I can still feel it deep within me.

If you listen to the recording, while the “we” was throughout, the moment where it was most profound was around 3:50—when the tension that had been building is suddenly released. The bass drops into a deep, sustained pedal tone, the sopranos soar into their upper range, and the tenors and altos fill out the harmony. That was the moment of knowing the sacred.

And by knew, I don’t mean intellectually. There was no rational explanation—only feeling. I felt the sacred, the mysterious, the transcendent, the eternal, the infinite, the beautiful, the true.

Even now, I struggle to put it into words, because words can never fully capture it. It’s like learning to play an instrument, to sing, to dance, or to move in perfect rhythm in a sport—you don’t truly know it until you feel it. And if you haven’t felt it, no words will ever be enough to explain it.

When the piece ended, the moment slipped away, and the loss was so intense that my legs buckled—I nearly collapsed from the shock of disconnecting from that sacred experience.

Breaking Atheism, Embracing Agnosticism

That moment shattered my atheism.

Up until then, I had been locked in a rigid framework—either theism (belief in a deity) or atheism (belief that no deity exists). But in that moment, I realized that neither fully encompassed what I had just experienced. I couldn’t claim belief in a deity, but I also couldn’t deny the reality of what I had felt.

From that point forward, I stepped into a more humble, open, and confused agnosticism—no longer certain of answers, but no longer closed to the mystery.

Finding My Way to Humble Agnosticism – My Time in the Bay Area

At the time, I didn’t realize it, but my year in Baltimore had been a sacred gift—one that allowed the fractured parts of me to begin growing toward resonance. This process, much like musicians tuning to one another, has taken time and continues to this day.

Even now, as I write this in 2025, I am only just beginning to align what I feel with what I can verbalize and make sense of. This search for understanding is what has called me to the work of "negotiating reality." But I’m getting ahead of myself, aren’t I? Back to the story…

A Journey Westward

With the gifts I received in Baltimore—finding the connection that led me to Andrea and my Chambers clan, discovering a direction for my research career, and experiencing a transcendent moment I couldn’t rationally explain but couldn’t ignore—I packed up my Honda Civic and moved across the country. I brought only what I could fit in the car and was joined by two friends, Harlan Weber and Spencer Johnson, on the journey. In doing so, I left behind many things, but one of the few I regret parting with was my djembe, a large hand drum that had been a cherished companion.

My first focus in the Bay Area was falling in love and growing together with Andrea, with the help of our dog, Cholla, who played a huge role in bringing us together. The Bay Area was a magical place for us—it had everything we loved: stunning landscapes, endless opportunities for exploration, and a sense of adventure that felt limitless.

Our first date set the tone for our life together. We drove up Route 1 through Marin County, stopping at Muir Woods, Muir Overlook, and eventually reaching Point Reyes before heading home. From that point forward, we explored every natural wonder we could find—the rugged coastline, the vineyards of Sonoma and Napa, the towering peaks of the Sierras, the majesty of Yosemite. We fell in love there, surrounded by breathtaking beauty.

Just six months later, I was ready to propose—ring in hand at Muir Overlook. But when I gently probed to see if Andrea was ready, she sent clear signals that she wasn’t. So, I waited. Instead, we got engaged at Lake Tahoe, about a year after we started dating.

Our love for the outdoors and adventure has continued ever since. At this point, I can confidently say we have visited nearly every major state and national park in California—except for Death Valley and the Bristlecone Pines, though we’ve driven past them several times. It’s only a matter of time.

Finding a Spiritual Home—For a While

As our relationship deepened, I began to feel an internal sense of confidence that allowed me to start making sense of my transcendent experience in Baltimore. Given what I had lived through, I could no longer embrace atheism—but I also had no idea what was true. That left me in a place of open-ended agnosticism.

Fortunately, Andrea, who was an atheist when we met, was open to exploring spirituality and wanted to do so together. That led us to the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto (UUCPA).

At the time, the church was exactly what we needed. It provided a space where we could engage in moral reflection and meaningful discussions. It allowed me to work through the contradictions that had drawn me away from traditional Christianity while also challenging some of the rigid assumptions that had once led me to atheism.

Building a New Framework for Understanding

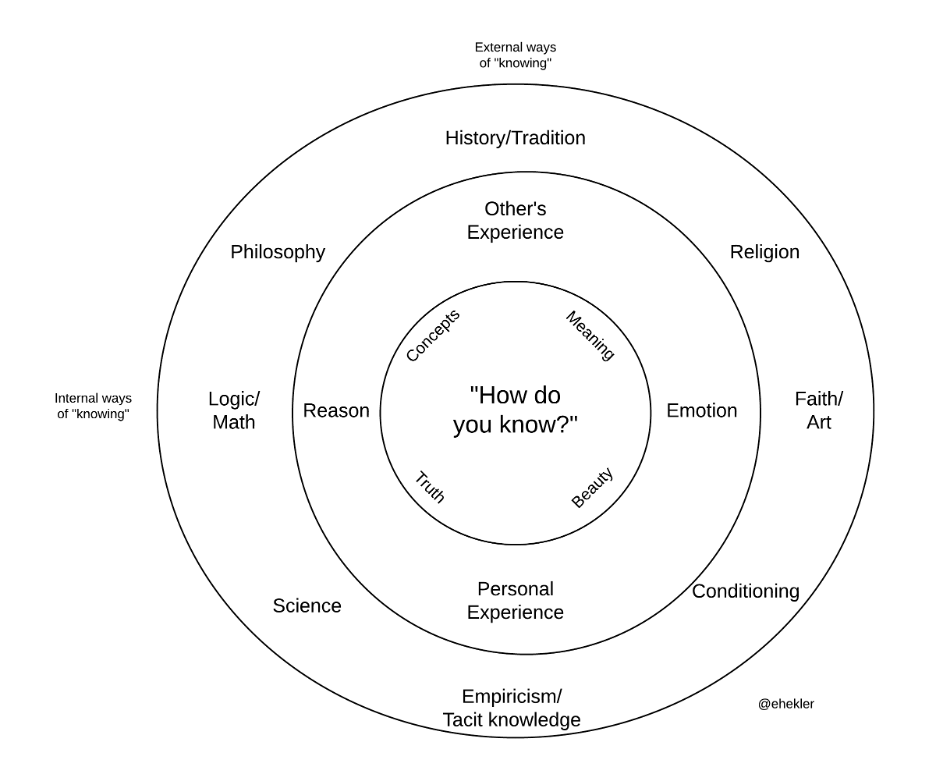

At UUCPA, I shared a personal epistemology map—something I had started formulating back in Baltimore. It helped me recognize that faith, art, and religion weren’t opposed to reason but were instead critical ways of knowing that complemented reason. They were essential to understanding the human experience in a way that reason/logic alone could never fully capture.

Through UUCPA, we were also exposed to a wide range of spiritual traditions, including Hinduism, Sufism, Judaism, Islam, and, importantly, a reconnection with the "good parts" of Christianity—particularly the core teachings of Jesus, such as those found in the Sermon on the Mount. We participated in working groups, Bible studies, and interfaith discussions, all of which helped us find meaning in different wisdom traditions.

However, there was a critical moment that shook me in a way I did not predict.

The Easter Service That Shifted Me (again)

During our last year in the Bay Area, we attended the Easter service at UUCPA. It started out beautifully. But as the sermon progressed, both Andrea and I felt that something was off.

Rather than celebrating Easter’s themes of renewal and grace, the sermon became a rational deconstruction of the Easter story. The pastor used the occasion to present a historical and practical case against the Resurrection—in essence, making an argument for secular humanism.

Andrea and I sat there, stunned.

Rationally, we agreed with much of what he was saying. These were ideas we had explored together before. And yet, something about the moment felt fundamentally wrong.

This was Easter Sunday—a day that, regardless of one’s personal beliefs, holds profound significance for millions and should be nurturing that sacred feeling. Instead of offering a message that honored the beauty of Easter and nurtured the sacred feeling of Easter, the sermon came across as lacking compassion and humility.

For the first time, I saw in the secular humanist worldview the same confident ignorance and emotional blindness that had once repelled me from religious dogmatism.

Andrea felt it too.

That day, we both came to the same conclusion: we no longer felt we could get what we needed at UUCPA .

This was a shocking realization—especially considering that we were leaving not because the church was too Christian, but because it wasn’t respectful enough of Christianity. If you had asked my college self to predict that happening, I’m sure my college self would have bet wrong. .

Life is full of mysteries, isn’t it?

A New Chapter: Moving to Phoenix

Not long after that Easter service, we left the Bay Area for Phoenix, where we lived from 2011 to 2017.

Phoenix became the backdrop for yet another transformation towards love in my life—the birth of our son, Elijah.

Elijah was born on November 19, 2013. From that moment on, Andrea and I understood—on a level we had never known before—that life was no longer just about us. Like all new parents, we grew into the realization that our purpose now included loving, nurturing, and caring for this new life.

More than anything, we began to truly experience and be guided by unconditional love. It’s a phrase easily spoken but a reality that requires profound commitment.

To be human is to live in the full spectrum of experience—the joys, the hardships, the moments of clarity, and the times of struggle (see separate post on life). Unconditional love, by its very nature, is not circumstantial. It isn’t something to be granted when convenient or revoked in moments of frustration. It does not hinge on behavior, beliefs, or actions. It simply is—constant, unwavering, eternal.

And yet, as humans, we inevitably stumble. I certainly have. There are times when I fall into conditional love, responding to the moment rather than to the deeper truth of love’s constancy.

Still, Elijah’s arrival stirred something in me—a lesson, an invitation—to be led by love, not just in thought but in life, in action, in deed.

For me, this lesson found its fullest expression through music. From the day Elijah was born (and even now, though less frequently—he’s 11 as I write this in 2025), I have sung to him at bedtime. Over the years, my repertoire has spanned the American Songbook, classic musicals, folk music, classic rock, and pop, but classical music has remained central.

One particular influence has been Bobby McFerrin, especially his classical album Paper Music. Among the many songs I sang to Elijah, one held a special place: Andante Cantabile for Cello and Strings by Tchaikovsky, as performed by McFerrin. Nearly every night, this was the final song I sang. I invite you to listen to this breathtaking piece here—and perhaps, someday, I will record my own a cappella version of it.

This song became more than just a lullaby; it was a ritual—a daily act of surrendering to and being guided by unconditional love. No matter what had unfolded that day, no matter my worries about the future or any tensions that may have arisen between me and Elijah, this song anchored us. It was our shared return to love.

With this, our years in Phoenix became wholly devoted to parenthood—learning, growing, and embracing all that came with it. Most of all, we embraced love and life in their fullest forms (see sister piece).

Compassion as the Path to Aligning My Heart and Head (2018–2024)

By 2017, I had reached a turning point in my research career (see sister piece). I realized that my focus needed to expand beyond just supporting personal health—I needed to also consider communities and environmental transformation. To contribute to, as my friend m.c. Schraefel says, “to make normal better” for everyone, in every community, everywhere. With this shift in perspective, Andrea, Elijah, and I moved to San Diego in the fall of 2017. There, we reconnected with friends and family and encountered new ways of thinking about spirituality.

Finding Spiritual Guides Next Door

Early on, we met our dear neighbors, Nancy and Phil Fowler, and their daughter, Katie. Over time, they became like family—parents to us and grandparents to Elijah.

Spiritually, Nancy and Phil’s journey was deeply shaped by profound loss—their son, Nicholas, died by suicide. His passing sent shockwaves through their lives, and they have been navigating that grief ever since. While this is their story to tell, its impact on us was undeniable.

After Nicholas’s death, Nancy pursued a pastoral degree at Claremont University, where she focused on compassion-based practices for grief and healing. Her mentor, Frank Rogers, leads the Center for Engaged Compassion at Claremont, and through her, we were introduced to his work. She gave us a copy of his book, Practicing Compassion—a book that would later influence my approach to compassionate critique (which I reference elsewhere).

Through Nancy, I also learned about a workshop led by Christopher Carter and Seth Schoen, who had developed a compassion-based approach to anti-racism. I attended their three-hour session, and though I didn’t yet realize it, this experience planted a seed that would continue to support my spiritual growth.

2020: A Year of Reckoning and Redirection

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, followed by the murder of George Floyd, the world—and my own understanding—shifted, yet again.

That same year, UC San Diego founded the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Sciences (HWSPH), and I was honored to serve as a Founding Faculty Member and the Founding Associate Dean for Community Partnerships—a role made possible through the invitation of my friend and colleague, Dean Cheryl Anderson.

2020 was an intense year to launch a new school of public health. Floyd’s murder sparked a national racial reckoning, and Cheryl sought meaningful ways for our school to respond. She invited the Assistant and Associate Deans to share ideas, and I brought up my experience with Christopher and Seth’s compassion-based anti-racism program.

Cheryl was deeply moved—both by their focus on compassion as a foundation for racial healing and by the fact that the program was co-led by a Black man (Christopher) and a white man (Seth). After further discussions, she invited them to train our leadership team and later expand the program schoolwide. I was part of the first cohort and remained actively involved in supporting its implementation.

Compassion as a Pathway to the Sacred

Engaging with the compassion practices offered by Christopher and Seth gave me the strategies I had been yearning for—practices I didn’t even know how to seek out. Through them, I found calm, clarity, and guidance, allowing me to navigate life in a more centered way. Christopher and Seth became mentors, offering one-on-one support that was instrumental in my spiritual formation.

During their course, one assignment invited us to engage in compassionate exploration, specifically turning inward to discover the “inner stirrings” that inspire, guide, and deepen understanding. Once again, music emerged as my guide—this time in the form of a musical.

These contemplative exercises unfolded across multiple sessions, and thankfully, I documented them contemporaneously (August 2020). The first major insight arose from an anxiety Christopher and Seth shared—one that resonated with me. They worried that the entire practice rested on an individual’s capacity to “sense the sacred” and be guided by it. In their teachings, as well as in those of their mentor Frank Rogers, they emphasized that sensing the sacred manifests in countless ways, shaped by culture and spiritual lineage. Given that we all came from a Christian background, we focused on grace—the power of love, care, and forgiveness as a pathway to transformation, especially when least deserved.

Here are some excerpts from my reflections at the time, lightly edited for clarity:

“I feel deeply struck by your anxieties about advancing this practice without a foundation of sacredness. It feels like this is precisely the moment when faith—broadly defined, not necessarily in a purely Christian sense—is needed most. And yet, as we’ve discussed, faith has been something I’ve struggled with. Interestingly, Christopher’s invitation to honor the great sacred mysteries in my spiritual practice has stirred something within me—a felt calling, an eventual understanding I am still reaching for. I am beginning to understand why you are so concerned about excluding a spiritual dimension from this discourse. Without it, there is no foundation. No ‘ground.’

And yet, paradoxically, embracing the great mysteries—those that will always be larger than me—is deeply comforting. I have faith in my smallness in relation to the awesome power and sublime experiences I’ve encountered. This realization has made me question something I’ve held onto for a long time: the Enlightenment project’s promise of certainty, the idea that if we work together through ‘the scientific method,’ we can arrive at definitive answers. There is wisdom in that approach, but it can only function if we remain aware of—and in touch with—the vastness of the unknown. I think of knowledge as the surface of a sphere. As the sphere expands, so too does the surface area touching the unknown. Without an awareness of that boundary, one can get lost within the illusion of certainty. It fosters confident ignorance, emotional blindness, entitlement, and epistemological traps. To be called to humility, curiosity, and compassion, one must engage with the Great Mysteries.”

During this period, a conversation with Seth led to an insight that shook me to my core: Rejecting one’s own lineage—especially from a place of privilege—is itself an unexamined privilege.

For years, I had distanced myself from my Christian roots, believing that rejecting them was an act of critical thinking and independence. But was it? Or had I simply never done the deeper work of understanding what I was rejecting and why?

This realization, combined with the racial reckoning of the summer of 2020 and my own complicity in systemic structures, created fertile ground for introspection. As part of the course, we were given a prompt to explore wisdom:

“Describe what you have learned for your life—your understanding, your practice, your actions, your studies, your vocation, your spirituality, and your longing for the good of yourself, others, and the world. Why is this important to you?”

Here are some excerpts from my response that relate to attuning to love (other insights on life are shared in a sister post):

“I feel a deep calling for spiritual growth because I don’t think my well is deep enough. I seek ways of being that allow me to touch sacredness, but the familiar pathways I’ve relied on leave me longing for more. I feel this most acutely in my music. I sing, I play piano, but lately, it feels hollow… I feel a stirring, a need for connection to sacred stories, texts, and traditions that feel rooted, aligned, and synergistic—not separate from but part of something larger.”

This week, that stirring manifested as sadness. My inner world was filled with hopelessness and pain. I initially resisted, but by midweek, I made a U-turn:

I see you, sadness. I am experiencing sadness. And that’s OK.”

The rest is a retelling as it was a long post. =)

Rather than avoiding it, I decided to engage with my sadness. And so, I turned to Les Misérables.

I have a long history with this musical; I know it intimately. That week, I let myself fully feel its sadness. I wept during Fantine’s I Dreamed a Dream, Eponine’s A Little Fall of Rain, and the devastating loss of the revolutionaries. But I also cried in places I never had before.

I wept when the priest forgave Jean Valjean and gave him the silver. I had always understood that moment intellectually, but this time, I felt it. I felt Jean Valjean’s suffering, his unworthiness, and the radical grace extended to him. I felt the overwhelming power of love and compassion as a force for salvation.

I also wept for Javert. He had spent his life devoted to order, rules, and certainty. He could not fathom a world where mercy, grace, and love overruled justice. When Jean Valjean set him free, he was offered an invitation—to embrace redemption through love rather than through law. But he couldn’t accept it. It shattered his understanding of reality. He had no framework for uncertainty, no tools to hold the sublime. And so, he chose death.

For the first time, I saw in Javert a reflection of my own struggles—the craving for certainty, the fear of collapse when confronted with the unknown.

Through Les Misérables, I found a new way to honor my lineage. I saw in Jean Valjean and Javert two sides of the continuum of Christian spirituality—grace and order, love and law. I saw the way attachment styles shape our ability to receive love, how insecurity can drive the need for rigid structures, and how the inability to embrace uncertainty can be devastating.

While these realizations emerged through story, I know they only truly “worked” for me because I embodied them through song. And yet, at that time, music itself felt hollow to me. Still, I worked through it, searching for my grounding.

Music has always been my way of “getting it out.” I have a wide vocal range, allowing me to sing Les Misérables songs in full voice, regardless of the character’s gender. That week, I sang I Dreamed a Dream to feel (in a very limited and superficial way) the suffering women have endured at the hands of men. I sang the priest’s act of forgiveness as an embodied experience of grace. I sang Bring Him Home as a commitment to love and sacrifice. And, of course, I sang Stars, Javert’s ode to order and certainty.

Through song, I allowed myself to confront the shallowness of my previous engagement with Christianity. I realized that for much of my life, my spiritual work had been intellectual rather than experiential—except, perhaps, in music. I had explored ideas but had not truly lived them.

This period of growth was about bridging that gap—learning to hold both the rational and the sacred, the scientific and the spiritual, the individual and the collective.

It was about compassion—not as a concept, but as a practice, a discipline, and a way of being.

Re-Anchoring in Music: Joining the San Diego Master Chorale

After this time, I finally felt called back to choral music. Thankfully, San Diego is home to many exceptional choirs. I auditioned for and was accepted into the San Diego Master Chorale, which felt closest to what I had experienced with the Baltimore Choral Arts Society.

Singing with them in the 2022–23 and 2023–24 seasons has been a profound gift. While my family and I are currently living in Kingston, making it impossible to participate this year, those seasons provided a crucial anchor—one that ultimately guided me back to the sacred through music.

Attuning to Wholeness Via Resonance Between Spirituality and Science – 2025 and Beyond

A critical model for me came when I read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass.

Kimmerer modeled a way forward—a method of “braiding” together seemingly distinct cultures and ways of knowing; demonstrating that when held in healthy resonance, seemingly disparate traditions can strengthen one another. Through her life journey, she showed how indigenous wisdom and practices can be woven together with Western scientific traditions, forming something richer than either could be alone.

Her approach provided me with an analogous model for what I feel called to do.

In my case, this braiding involves finding ways to create healthy, diverse resonance between Western spiritual and religious wisdom traditions and Western scientific and philosophical traditions. But given our interdependent, interconnected world, this work cannot be limited to just Western culture. It feels increasingly critical to also play a role—however small—in fostering the conditions for cross-cultural wisdom exchange, where diverse traditions are not competing or exploiting one another but instead aligning for mutual flourishing. With this, I seek to learn from, without colonizing or claiming expertise in, other wisdom traditions, such that, together, we might grow in health relation together.

Some other key people shaping my spiritual journey

This attuning to wholeness—of integrating spiritual depth with scientific rigor—has been shaped by many, as already described, such as my mom, Andrea, Elijah, Nancy, Christopher, Seth, and others already mentioned. There are four additional close friends I must mention as well, as they have also been critical, particularly since my move to San Diego:

Kabir Kadre, a steadfast spiritual guide, has helped me navigate my evolving awareness and its implications for responding to the broader meta-crisis. We collaborate through Open Field Awakening, the non-profit he founded.

Pradeep Gidwani has been instrumental in exploring how healing relationships, rooted in spiritual connection, can be integrated into our healthcare systems to promote collective well-being.

Nadaa Taiyab introduced Andrea and me to the Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) and the teachings of Paramahansa Yogananda. We are now both active disciples, drawn to SRF’s unique blend of Eastern and Western spiritual traditions, which weaves together the teachings of Jesus and the Bhagavad Gita to cultivate a direct experience of God.

Dan Seward, an old friend from undergrad, has been a deep source of wisdom. Raised Jewish, Dan remains connected to his roots—attending synagogue, embracing his heritage—but has also immersed himself in yogic traditions. With Dan, I have a friend who has known me through much of my journey. We don’t just discuss these ideas abstractly—we live them together, drawing upon our shared history and evolving perspectives.

I am deeply grateful for their wisdom and for the ways they continue to shape my path.

Integrating Spiritual Practices into My Life and Work

This journey has allowed me to start to learn how to honor my Christian roots while also embracing spiritual practices that I struggled to find in traditional church settings. With all of this, the central guide is unconditional love. Spirit’s way, if you will.

These experiences have significantly influenced not just my personal growth but my professional work—shaping the way I engage with procedural and spiritual practices, and ultimately, how I have come to see the work of negotiating reality as an ongoing, communal process.

As the story shows, a big part of spiritual development, for me, is to attune to and be guided by divine, unconditional “big” love. The kind of love taught by Jesus and Yogananda. The type of love I felt and feel through music. The type of love that is the foundation of being a parent.

A Song to Close: O God Beautiful

I want to end with a song that has become meaningful to me from SRF: “O God Beautiful” (Listen Here; and, note, I plan to eventually record myself singing this and putting that up here).

This cosmic chant, central to SRF’s tradition, is one I often find myself singing when I need to reconnect with the sacred, the beautiful, and the transcendent. I feel it resonant not only with SRF, but the Celtic Christian lineage as described here (and introduced to my by Frank Rogers, the creator of the Compassion Practice described above)

. When I need to anchor to unconditional love, this is a go to chant for me.

I hope this song brings resonance or comfort to you. But if it does not, that’s OK! We are likely coming from different lineages, life experiences, and the like. The forms that anchor me to unconditional love may not be the forms that work for you. That’s OK!

I would love to hear from you—what music, what practices, what experiences help you feel connected to sacred unconditional love?