The Evolution of My Research Career

From Advancing Methods to Improve Personal Health to Advancing Methods to Improve Holistic Health

Since the beginning of my research career, collaboration has been at the heart of my work. I have never pursued any of my work alone—each endeavor has been shaped by the insights, expertise, and support of incredible colleagues and friends. Indeed, I have found that, often, I seem to do my best work when I am the “number 2”. Actively there and fully “in” while also not the primary one driving things.

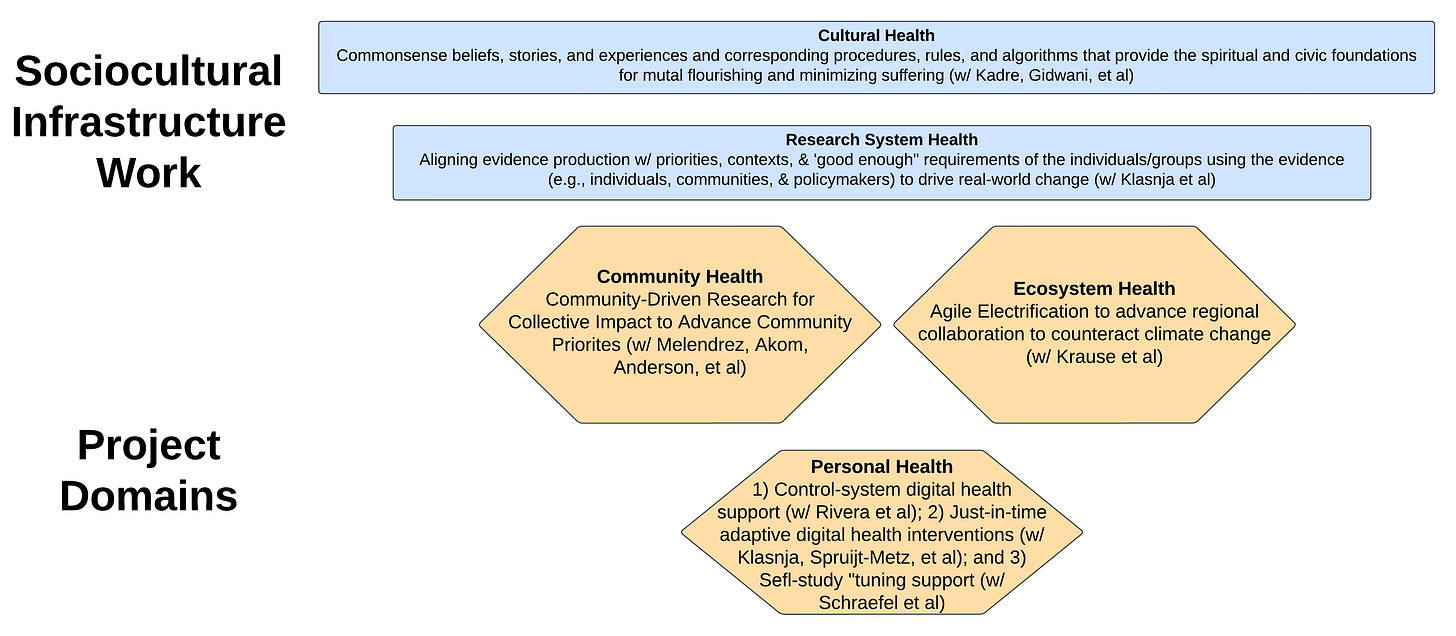

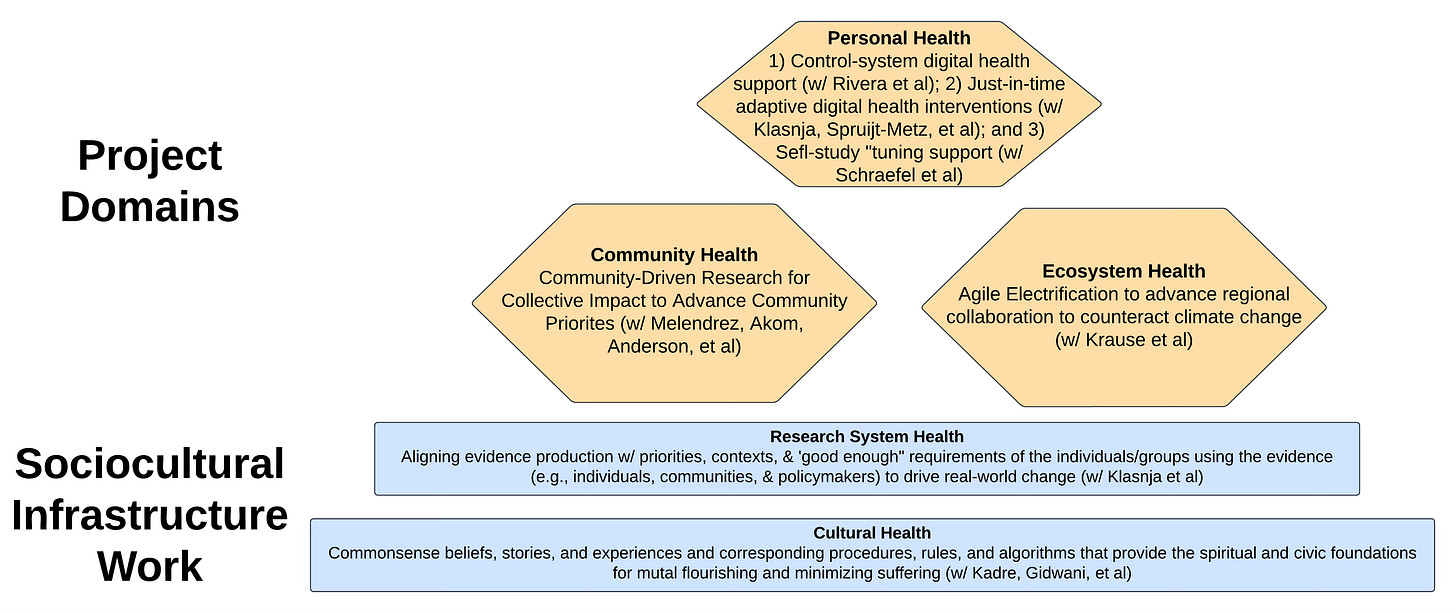

My journey has been one of continuous evolution, growing from a foundation in digital health to a transdisciplinary approach that now encompasses personal, community, ecosystem, research system, and cultural health.

This trajectory began with a focus on personal health, leveraging digital tools to improve individual well-being. Working alongside Daniel Rivera, Pedja Klasnja, Donna Spruijt-Metz, m.c. Schraefel, and others, with early support from Wendy Nilsen, I sought to harness technology to empower individuals in their health journeys. From there, my work quickly expanded to improving the health of the research enterprise itself, ensuring that health sciences research aligns with the priorities and needs of the people and communities it serves. My collaboration with Pedja Klasnja, with early guidance from Paul Tarini and Steve Downs, was and is instrumental for this line of work.

Recognizing that personal health is inextricably linked to the health of our natural world, I was drawn into ecosystem health through my friendship with Andrew Krause. Together, we have worked on projects focusing on collective action, community organizing, and industry-led solutions to drive sustainable, equitable, and carbon-neutral systems. Around the same time, my collaboration with Dana Lewis, Erik Johnston, John Harlow, and others deepened my awareness of the limits of good intentions. I came to understand how "normal" systems and structures often perpetuate harm (both by design and unintentionally). This realization, coupled with a recognition that many people I was seeking to support via personal health struggled because the vital conditions of health were not there compelled me to focus on community health—working with Blanca Melendrez, Cheryl Anderson, Antwi Akom, and others to ensure that research methods are truly community-driven, aligned with local needs, and supported by the right expertise from academia and beyond.

Most recently, I have been drawn toward fostering cultural health. With this, I recognize how the sociocultural foundations enable the other aspects of health, just as personal health enables people to work together on the other parts. For me, I see all of this work as necessary to understand and advance the “healthy breathing” that is holistic health. A healthy flow of actions that support personal, community, ecosystem, research enterprise, and cultural health, flowing back and forth.

Training to Become a Researcher

Several pivotal moments shaped my journey into research. My path began with my doctoral training in clinical health psychology at Rutgers University under the mentorship of Richard Contrada. Richard’s guidance instilled in me a deep respect for rigorous research methods and the balance between theoretical and practical contributions—an ethos that continues to define my work.

I earned my Ph.D. in 2008, just as the iPhone was revolutionizing personal technology. A conversation with a friend, Jamie Naifeh, sparked an idea: could a phone's accelerometer be used to track physical activity and support behavior change? That moment, though naive in hindsight, set me on a path toward mobile health interventions.

This idea led me to Stanford University, where I worked with Abby King, a mentor who gave me the freedom to explore. She connected me with the Stanford d.school, where I was introduced to human-centered design through collaborations with Banny Banerjee. Around the same time, President Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) provided NIH funding that allowed Abby and me to secure a grant for the MILES project—one of the first studies using smartphone apps to promote physical activity among older adults.

Through this work, I confronted the complexity of human behavior. While our randomized controlled trial showed that social engagement (see here and here) was the most effective motivator, qualitative data underscored that different people need different types of support at different times. Abby called this the "which'es conundrum"—which intervention, for which person, at which time, and in which place? This challenge sparked my interest in advancing personalized, adaptive interventions.

Advancing Personal Health

My work in personal health has unfolded across three broad domains: control-system digital health, Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs), and self-study/tuning support.

In 2011, I attended a talk by Daniel Rivera, a control systems engineer applying engineering principles to behavior change. Intrigued but struggling to grasp the concepts, I sensed their potential. By another stroke of luck, Arizona State University had a faculty position in a sister school to Daniel’s, and I secured the role, joining ASU alongside my research brother, Matt Buman. Daniel and my collaboration flourished, leading to a body of work integrating control systems engineering into behavioral health research—a line of inquiry that continues to thrive today.

That same year, I was invited to a workshop at the University of Michigan hosted by Susan Murphy and Inbal Billie Nahum-Shani, where they introduced the concept of JITAIs. I immediately saw the alignment with my work and deepened my collaboration with Pedja Klasnja (who is also at Michigan), whom I now consider my “research spouse.” Our work led to methodological advancements in micro-randomized trials and the development of agile science (described more below).

This work was further supported and strengthened through mentorship, support, and active collaboration with Donna Spruijt-Metz, who was my mentor at the inaugural mHealth Training Institute. Donna has been a steadfast mentor, friend, and colleague and, along with Pedja, and many others, have been working together for some time to bring this vision of JITAIs into reality.

While I found (and continue to find) value in that work, as I engaged in this line of work I started to become more and more aware of the potential unintended consequences. If we weren’t careful, we could be building tools of manipulation…driving people to our goals for them, not theirs. With this recognition, working with others, particularly Camille Nebeker, we have sought to examine and reimagine the ethical, legal, and social implications of digital health, to ensure our tools are aligned with individual’s priorities and goals, can fit well within their contexts, and can adapt to their local needs and conditions. With this, we always seek to be responsive to a central guiding assumption I make in my work: People are different. Context matters. Things change.

With all that said, early on I became interested in exploring ways to “help people help themselves” as a possible way to build “checks on algorithms.” That line of thought drew me into the Quantified Self movement, where I connected with Gary Wolf, Ernesto Ramirez, Aaron Coleman, Kevin Patrick, and others.

This work, coupled with a semi-chance meeting several years ago at a conference I helped organized in Germany, helped pave the way for my on-going collaboration with m.c. Schraefel on the concept of “tuning”—a framework for self-experimentation to support individuals in cultivating knowledge, skills, and practices to improve their health (see here ).

“Tuning, in the context of [supporting individual health], is much like becoming resonant and harmonic with oneself and one's context, and simultaneously can involve engaging in actions that tune up the body to enable positive adaptation in context. In terms of the inbodied interaction framing of the body as the site of adaptation, adaptation is the automatic response of the nonvolitional inbodied processes overall; tuning is the set of volitional acts one engages in to effect adaptation. A key takeaway is that, as with an instrument or an engine, tuning is active and dynamic: It is regularly required since both use of the system and the environment in which that system sits impact the degree to which tuning is maintained.” - m.c. Schraefel & Eric Hekler, Tuning: An Approach to Support Healthful Adaptation

With this, our work is really focused on cultivating a person’s capacity to "feel” and know what it “feels like” to live healthfully and, with that as the central guide, support them in trying out different options that have worked for others to help them improve whatever it is they feel drawn to improve, such as physical activity, diet, sleep, connecting with others, or thinking (what mc calls the “in5” as basic behaviors that we all seem to need to live and thrive). This work is gradually growing and connecting with my community work via Steven De La Torre as our bridge connect me, mc, and Antwi Akom (mentioned below).

Improving Research System Health

In 2013, based in part out of growing discussions with Pedja, I had the opportunity to give an “Ignite” talk about the concept of Agile Science at a Health FOO event. This caught the attention of Paul Tarini and Steven Downs, leading to a grant that supported the exploration and development of Agile Science as a framework for making research more decision-focused, timely, and impactful in collaboration with Pedja Klasnja.

This work continues today, in collaboration with Pedja and others, with work exploring and development models for advancing precision health, epistemic inclusion, and, most recently, the development of a framework to support more effective coordination of researchers to ensure research is being produced that meets the needs of those who will benefit from the research. We are currently calling this framework decision-focused evidence production.

This work critically examines, reimagines, and reconfigures the often implicit assumptions and core beliefs that underlie all other research efforts.

To illustrate as an analogy, I often refer to David Foster Wallace’s famous commencement speech, This is Water. In it, he starts with a story of two young fish who do not recognize that they are swimming in water—until an older fish points it out. This metaphor resonates deeply with my foundational work. Many well-intentioned researchers, acting in good faith, may not recognize the “water” they are immersed in. If the water is healthy, that may not be an issue. But what if it’s polluted?

Image from

By analogy, my foundational work—including the work Pedja Klasnja and I have termed "agile science" and, more recently, "decision-focused evidence production"—is about understanding and improving the quality of the water in which scientists operate.

We are particularly focused on articulating frameworks and structures that support researchers working in our domain (behavioral and community health) in selecting the right research methods—those that are:

Aligned with the priorities and goals of the evidence users, with particular attention to how different methods serve distinct groups:

Individuals and their unique needs for guiding decision-making and thinking over time (this is the core focus of two of my three core project areas, the one with Daniel and the one I’m about to describe focused on self-study)

Communities, and healthcare organizations, whose place-based contexts are critical to take into account when producing solutions and evidence to support their decision-making needs (this is the core focus of my community-driven research work with Blanca Melendrez, described next).

Policymakers, who operate at level of abstraction that is necessary (e.g., supporting the development of general guidelines and evidence-based recommendations) but also insufficient when used alone (this has, classically, been the primary focus for evidence production within health sciences research).

Attuned to contextual circumstances, considering both the unique strengths and challenges that influence an individual or group's ability to achieve their goals.

Calibrated to what is “good enough” in evidence production—balancing rigor with practical constraints. This ensures that research meets the needs of its users, whether insights are required in weeks rather than years.

I’m actively working on the paper describing and drawing this all together (and giving a master lecture on the topic in March at the upcoming Society of Behavioral Medicine Conference, which is my "disciplinary home” where I was supported and “grew up”).

Advancing Ecosystem

At ASU, my role as a Sustainability Scientist connected me with colleagues in sustainability research. This laid the foundation for my ongoing collaboration with Andrew Krause. We have been working for some time on a range of projects. Given this is already long, I’ll mention our most recent project, which is called the Agile Electrification Project. In it, we seek to create scalable, community-driven solutions for climate resilience via solar-first electrification.

Good Intentions Are Not Enough

A pivotal moment in my journey occurred at the 2016 Quantified Self Public Health Symposium, which was recorded and remains publicly available. At this symposium, Dana Lewis and eight others presented their groundbreaking work on creating an open-source artificial pancreas system (OpenAPS). At that time, 59 individuals had developed their own OpenAPS rigs. While I don't know the exact number today, I am confident it has grown into the thousands based on the last count I heard from Dana.

This work translated into a collaboration together that has had a profound personal impact on me. I later reflected on it in a blog post for an RWJF-funded project that Dana, Erik Johnston, John Harlow, and I collaborated on our shared project called Opening Pathways for Innovation. This project aimed to support non-traditional researchers—individuals with real-world expertise—who were driving innovation. Dana and her now-husband, Scott, embody this movement, having co-created the first Open Artificial Pancreas System.

I encourage you to explore our work on the Opening Pathways website, where we developed blog posts, a patient innovator toolkit, a partner toolkit, and other resources designed to foster this type of research and engagement.

Collaborating on this project with Dana and others was an eye-opening experience for me personally. It heightened my awareness of the limitations inherent in traditional research structures. Historical precedent, unexamined social norms, and entrenched systems often prevent those with the most relevant knowledge from being recognized as experts.

This realization led me to question the very nature of what is considered "normal" in research and science. I came to understand how existing structures not only fail to support innovation but also create epistemic blindness—a systematic disregard for alternative ways of knowing and doing. Without explicit malice, those granted authority within the system are often unaware of how their privileges prevent them from recognizing other valuable perspectives.

This experience fundamentally shifted my worldview. I realized that good intentions alone are insufficient to drive meaningful change. I felt this lesson deeply, both intuitively and practically: even with the best of intentions, I could still contribute to harm if I wasn’t actively working to dismantle these structural limitations. I described this in a post, which can be found here: Saving Mr. Scientist.

Advancing Community Health

Recognizing that individual health is deeply shaped by community health and other structural factors, I shifted my focus toward community health upon joining UC San Diego in 2017. A transformative partnership with Blanca Melendrez and the Center for Community Health enabled us to reimagine how research could center community voices.

This work has been further supported by Dean Cheryl Anderson and our work together on creating new structures and approaches within our School of Public Health that centers and prioritizes community priorities and advancing public health practice in the real-world.

In addition, this work was strengthen via a collaboration with Antwi Akom, who developed the Streetwyze platform. Together, we (Antwi, Blanca, Cheryl) and others, such as Tessa Cruz, Lilana Osorio, Earl Felisme, Shana Wright, Lan Nguyen, have been developing approaches for centering community voice with collective impact efforts with the use of Streetwyze.

Most recently, this team, in collaboration with Aimee Zeitz and others from the YMCA, and our community leaders, including Earl Felisme, Tana Lepule, and Rocina Lizarraga, have, together been awarded an American Heart Association Grant focused on advancing a place-based community-driven research to action paradigm that will be focusing on advancing food justice in San Diego County (a topic identified in our prior work, via the use of Streetwyze).

Toward Cultural Health

As I look to the future, I see cultural health as the part that is currently breaking down. I’m using my time on sabbatical to start to develop a structured approach whereby, over time, I can find ways to contribute towards fostering cultural health, in a way that is resonant with my other activities, hence this substack space and the podcast, Negotiating Reality.

A healthy culture serves as the foundation upon which individuals, communities, ecosystems, and research systems can thrive. Without cultural health, all other health domains suffer. With that said, I also see this as like healthy breathing: working on fostering healthy communities, ecosystems, research systems, and cultures, requires healthy individuals, capable of showing up, thinking, playing, re-imagining, and acting differently living in healthy communities and ecosystems.

Putting it all together

The common themes across my research include:

Mutual Flourishing & Reducing Harm: Striving to create systems that foster well-being while minimizing exploitation.

Honoring Agency & Autonomy: Ensuring that solutions support individuals and communities and are aligned with their priorities and goals rather than dictating their actions.

Commitment to Life (improving things in the real-world): Engaging in research that prioritizes practical application over academic abstraction.

Context-Sensitive Methods: Recognizing that health happens in the real-world and thus, local strengths and challenges must be taking into account to advance health.

Philosophical Inquiry: Continuously reflecting on the ethical, epistemological, and ontology foundations of my work.

Thus, my life's work is dedicated to fostering the methods and processes that advance holistic health—advancing knowledge, methods, and systems that enable people, places, and the planet to flourish together with healthy breathing flowing back and forth between supporting personal, community, ecosystem, research system, and cultural health.