The Four Elements Epistemic Model (prototype)

A framework meant to help people understand one another from across different cultures and ways of knowing

An Invitation to Dialogue

What follows is a hypothesis—a proposed framework for understanding how we come to know what we know. It is not a final answer but an offering for rigorous examination and critique, particularly with future audio episodes and corresponding discussions meant to unpack all of this to invite shared discourse. This framework has been implicitly guiding my thinking since I (Eric) started this podcast (see the very bottom to learn how this model is actually represented in the core visual for this Negotiating Reality space). This is also a rough draft starting point of a roadmap that I plan to make the core focus of Season 2 of Negotiating Reality. I’m putting it out now as I’ve been increasingly asked by some listeners, back channel, to be even more transparent and explicit about my epistemic assumptions to help provide a structure for understanding the metaphysical and teleological claims that are being explored right now in Season 1 of the podcast. As I flagged previously, this is very much a chicken-and-egg issue whereby all of these explorations into facets of a worldview (the nature of reality, orientations around meaning/purpose, descriptions on how we know what we know, and understanding on being, becoming, and doing) are referential to one another and thus, even when focusing on one facet of a worldview, all the other facets need to be brought in, at least in a cursory way, to enable understanding.

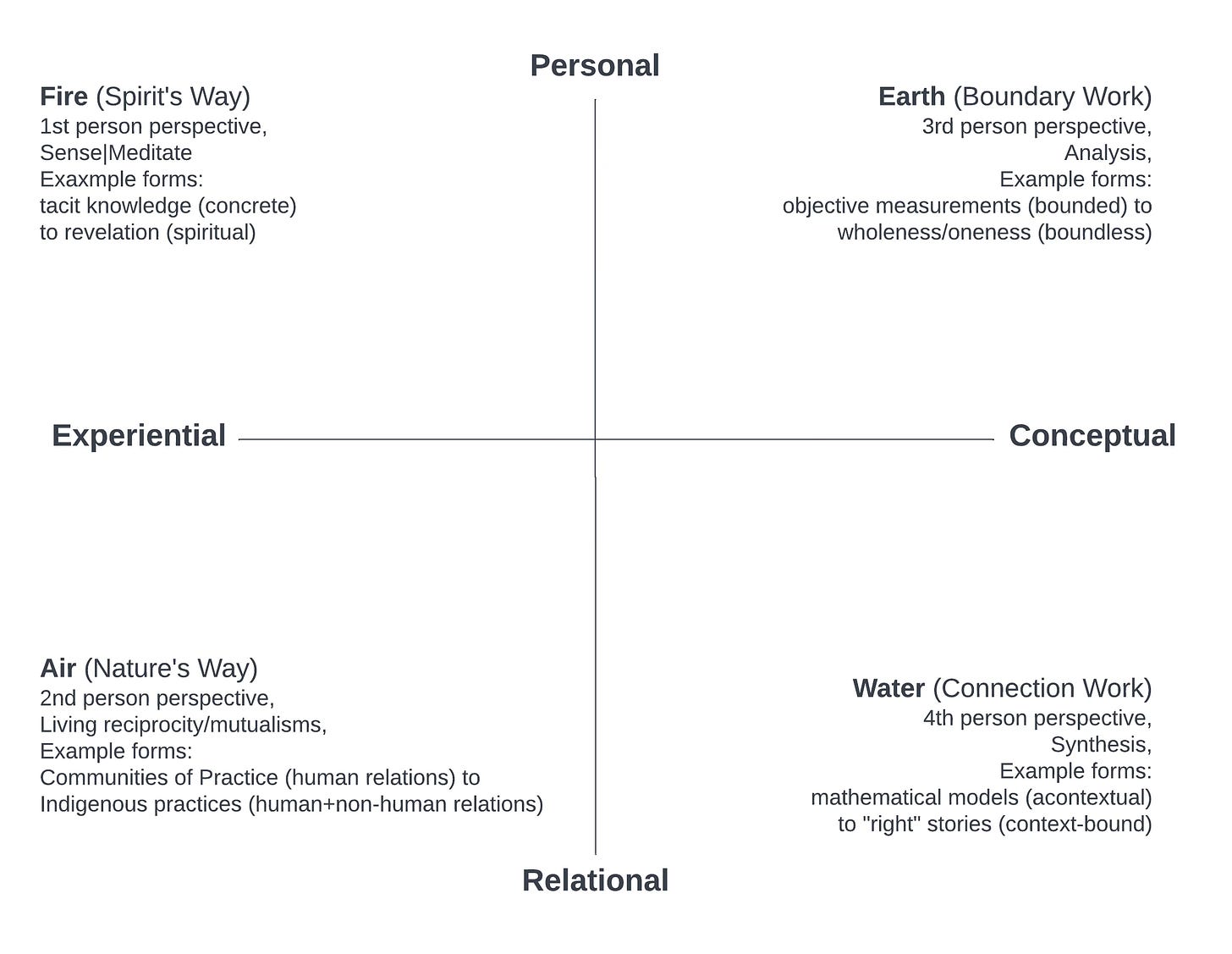

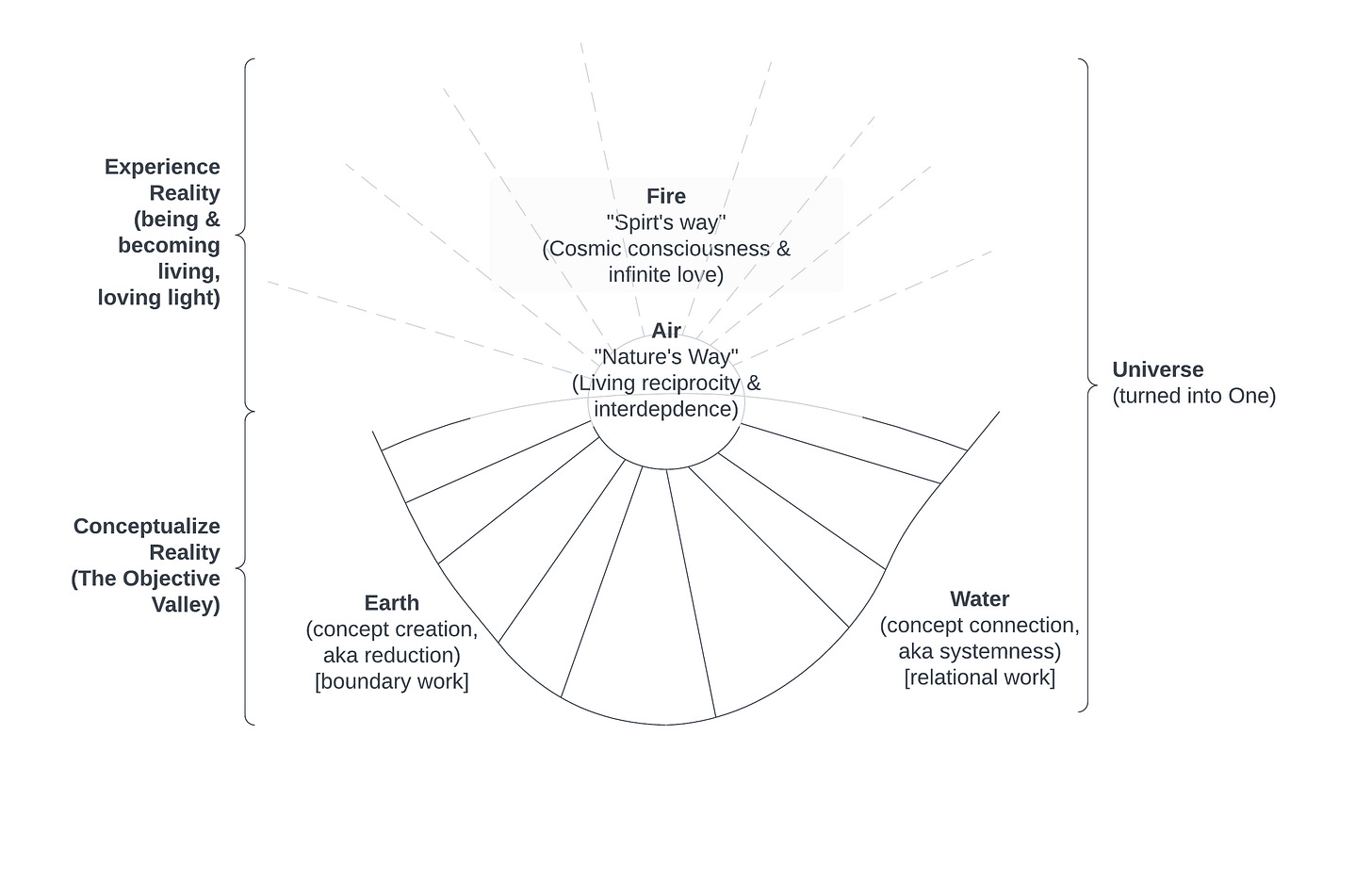

This framework organizes four complementary ways of engaging reality along two fundamental dimensions and, critically, while I (Eric) was the primary author, my three co-authors, Kabir Kadre, Chag Lowry (Yurok, Maidu, and Achumawi ancestry), and Steven De La Torre provided critical review and commentary and suggestions on this framework prior to publication. Specifically, Kabir provided critical review and feedback on “Fire” quadrant (as well as interpreting and building on prior Integral work, in the sister piece described below). Chag provided critical review and feedback on the overall piece and, in particular, the “Air” quadrant, given its strong orientation towards building on and honoring Indigenous epistemologies. Steven De La Torre played a critical role in drafting the foundational assumptions and, in particular, the notion of epistemic fit. Whenever there is mention of “I” it is Eric writing. When it is “we,” it is representing a perspective from at least two (and at times all) of the co-authors.

This framework was initially inspired by Ken Wilber’s Four Quadrants (see Finding Radical Wholeness) model for “showing up,” while not focusing on the elements oriented toward Wilber’s developmental focus. Rather than emphasizing stages of psychological or spiritual maturity (which is valuable and important in its own area and right)—the primary orientation of Wilber and other Integral Theorists—this framework concentrates on epistemology: it is a representational framework that provides heuristic structure for understanding how we, as humans, know what we know. The logic for this focus on epistemology is to serve the primary concern of this prototype offering, which is to help enable us to more deeply listen to one another on each of our own terms, or, to put it differently, to cultivate a set of agreements for holding our disagreements [this is flipping a phrase from James Davison Hunter shared in Episode 1].

A critical clarification from the outset: This framework is a representation—a conceptual map, not the territory. It is a heuristic tool for organizing understanding and facilitating dialogue, not an ontological claim about reality’s fundamental structure. The framework positions these ways of knowing as complementary aspects of how consciousness engages with what is, but it does not claim to have discovered four ultimate categories of reality itself.

What we offer is provisional, requiring dialogue with diverse epistemic communities for validation, correction, or revision. Your critical engagement—your questions, objections, and alternative framings—is not merely welcome but necessary for determining whether this framework serves its intended purpose: enabling more productive dialogue across epistemic divides.

When we make implicit assumptions explicit, we make them contestable, refine-able, and improvable. We engage in the process of creating faithful representations of reality that can be examined and interrogated by different humans, each bringing their own strengths, vulnerabilities, and unique vantage point. That is precisely what I seek here. I am attempting something ambitious: proposing a conceptual tool that might help us understand not just how we know, but why communities with different epistemic commitments so often talk past each other—especially in our current moment of cultural and political polarization.

Building on Wilber’s Foundation with Key Refinements

This framework explicitly builds on Ken Wilber’s Four Quadrants model, which has long sought to bridge epistemic divides between spiritual and scientific ways of knowing. However, we propose several refinements that make the framework more precise and useful for this epistemic focus (while still honoring the developmental focus of Wilber’s work, but not emphasizing it here):

First, we replace Wilber’s “interior|exterior” distinction with “experiential|conceptual” to better capture how we know (through direct experience and concepts) rather than implying a spatial location. This shift is grounded in converging insights from neuroscience (Lisa Feldman Barrett’s work, described in episode 4), contemplative traditions (the Dalai Lama’s arguments in The Universe in a Single Atom about phenomena like oneness that cannot be observed through analytical separation), and philosophy of science (Michael Polanyi’s insights in Personal Knowledge that all conceptual knowledge rests on experiential foundations).

Second, we replace “individual|collective” with “personal|relational” to emphasize that relational knowing involves genuine emergence—not just aggregation of individual knowledge—and to honor Indigenous epistemologies that understand knowledge as arising through sustained relationship with place and community.

Third, as already mentioned, we also separate this epistemic framework from Wilber’s developmental orientation. Developmental perspectives are really valuable and important and an area that deserves careful exploration on its own terms. Indeed, there is likely a great deal of possible connection and resonance between epistemic and developmental discussions, as suggested by Wilber (a point we support). Still, given our interest in fostering more effective communication, our sense is that, while these can be combined, that combination must be done thoughtfully and carefully. When that does not occur, it can result in muddling of communications and a veritable “Tower of Babel.” To try and reduce this risk of muddling up too many inter-related concepts, we are using an approach of trying to modularize our representational work, such that each facet of this can be engaged with on its own terms and in relation to the core focus of an inquiry, thus enabling a richness and depth of understanding in relation to a focal concern. As depth across focal concerns comes into being within a group, then these bridging discussions across concerns become more possible and, I (Eric) would argue, more fruitful as it is easier to have clarity on exactly what is being discussed and how to work through it. This disciplined focus on having clarity on the purpose of a particular discussion, bounding it to that concern/function, and then exploring it at sufficient depth before then connecting with a related concern is a key strategy that is being used across this Negotiating Reality space. Thus, that approach is also being brought to bear when engaging with Wilber’s work, hence the conscious separation of what we view as the key epistemic implications of Wilber’s framework from the developmental concern driving his work (in his work, development is the core concern and, thus, the epistemic elements, based on our read, is in service to that goal; a valid approach but distinct from our concern).

As clarity emerges in this epistemic domain, we would be very interested and excited to explore this with others (e.g., see comments already about this in the sister post). For now though, the primary concern here is a focus on how we know what we know with a particular focus on cultivating a framework that can aid people using different epistemic tools to be able to communicate more effectively together.

For a detailed exploration of these refinements and adjustments toward this epistemic concern (while honoring and recognizing as a distinct and valid and important concern, Wilber’s orientation toward understanding human development) and why they matter, see the companion piece:

This sister piece is particularly for those with prior knowledge of Integral Theory as well as those with more deep knowledge of Indigenous Epistemologies as we unpack our understanding of that critical way of knowing and how it was not, as far as we can tell, incorporated into Wilber’s framework. With these changes, we seek to honor Wilber’s foundational contributions while adapting the model specifically for bridging contemporary epistemic divides while trying to minimize any strong ontological claims about reality’s fundamental structure, though we are explicitly building on the metaphysical assumptions that have been laid out in Episodes Two, Three, and Four of this podcast (please listen/read them for more details as well as the follow-up negotiation episodes on each).

Foundational Assumptions: The Epistemic Commitments Enabling Cross-Quadrant Dialogue

Before presenting the four ways of knowing that comprise this framework, we must be explicit about the foundational assumptions we are making that, we contend, make cross-epistemic dialogue possible. These are not hidden premises but conscious commitments that invite challenge, refinement, and critique. Making them explicit allows them to be tested, improved, and ultimately validated or rejected through the rigorous dialogue this framework seeks to enable.

Three interrelated assumptions form the bedrock of this work: epistemic humility, the distinction between epistemic and ontological claims, and the principle of epistemic fit. Together, these assumptions establish the conditions for what we’ve called “agreements for holding disagreements”—the shared ground that makes productive dialogue possible even across profound differences.

Assumption 1: The Necessity and Cultivation of Epistemic Humility

Epistemic humility is both a precondition for engaging with this framework and something the framework itself helps cultivate through use. This creates a virtuous cycle: you need baseline humility to participate meaningfully, yet participation deepens that humility over time.

At its core, epistemic humility requires three interwoven capacities:

Humility about the limitations and boundaries of one’s own conceptual models, maps, systems, mathematical frameworks, or experiential understanding—however these are formed, whether through direct personal experience, relational experience with others, systematic scientific investigation, or revelatory insight. No matter how sophisticated our ways of knowing, they remain partial perspectives on reality, not reality itself. The map is never the territory, even if our brains are reliant upon the maps (see Episode 4).

Curiosity sufficient to genuinely seek to understand others on their own terms—not merely to tolerate their views but to deeply comprehend how they see the world and come to know what they know. This curiosity asks: “How does reality appear from your vantage point? What enables you to know what you claim to know?” It resists the impulse to immediately translate others’ claims into one’s own framework or dismiss them as simply wrong (this is a key counter-response to variations of Anthropomorphizing or its variants, which were discussed both with Bjornerud and Dunn).

Compassion that recognizes the legitimacy of other people’s experiences and ways of knowing, even when they differ profoundly from one’s own. Compassion doesn’t require agreement but does require acknowledging that others are genuinely trying to understand reality and live well, not operating from delusion or bad faith (though violations of good faith must be identified through patterns in sustained relationship when they occur, see below).

Critically, epistemic humility does not mean abandoning confidence in what one knows or retreating into radical relativism where all claims are equally valid. Rather, it means being simultaneously confident within one’s domain of expertise while humble about the boundaries of that domain and open to what other ways of knowing might reveal.

Why Epistemic Humility is Essential

Without epistemic humility, dialogue across epistemic divides becomes impossible. Consider what happens in its absence:

Scientists dismiss spiritual experience as “merely subjective” without genuinely understanding contemplative methods or what they reveal

Spiritual practitioners reject scientific findings as “materialist reductionism” without engaging with what measurement can actually establish

Indigenous knowledge keepers are told their place-based wisdom is “anecdotal” without recognition of the sophisticated methods underlying relational knowing

Systems thinkers become so enamored with their models that they lose touch with experiential reality

Each of these represents epistemic arrogance—the presumption that one’s own way of knowing is not just valuable within its domain but universally superior, capable of adjudicating all truth claims. This arrogance forecloses dialogue before it begins, and, sadly, was likely very prevalent particularly among individuals who implicitly or explicitly took an Orientalists perspective.

Epistemic humility opens a different possibility: that engaging seriously with other ways of knowing on their own terms might reveal aspects of reality invisible from one’s current vantage point. It creates conditions where a physicist might learn something genuine from a mystic about the nature of consciousness, where an Indigenous elder’s observations might refine a climate model, where a systems thinker’s framework might help a spiritual community articulate its practices more clearly.

The Both-And Dynamic: Precondition and Cultivation

The relationship between epistemic humility and this framework operates in both directions:

As precondition: Some baseline level of epistemic humility is necessary to engage meaningfully with this framework at all. If someone approaches with absolute certainty that their way of knowing is the only valid path to truth, they will not find value here. The framework requires at minimum an openness to the possibility that reality might be knowable through multiple complementary approaches.

As cultivation: Using this framework—seriously engaging with how different quadrants operate, attempting to understand other ways of knowing on their own terms, participating in cross-quadrant dialogue—tends to deepen epistemic humility over time. As one discovers the distinctive gifts of each way of knowing and recognizes how partial any single perspective is, humility grows naturally. The framework doesn’t just map existing humility; it helps generate more of it.

This creates what we might call a “virtuous cycle of understanding”: modest humility enables initial engagement, which reveals more of what one doesn’t know, which deepens humility, which enables more sophisticated engagement, and so on. Over time, participants become more capable of both confidence within their domains and humility about their boundaries.

Epistemic Humility and Cultural Evolution

Importantly, epistemic humility should not be confused with epistemic uncertainty or lack of conviction. There will always be—and should always be—people with strong certainty in their beliefs and ways of knowing. Some hold devout faith in the inerrant truth of sacred texts; others hold unquestioning belief that “science is real” as the pathway to all Truth. These forms of certainty manifest across all ways of knowing.

From an evolutionary and ecological perspective, this certainty likely serves valuable functions in cultural resilience. People with strong, certain beliefs challenge dominant norms and provide what might be called “healthy mutations” in the cultural ecosystem—variation that contributes to population-based resilience and adaptability over time, much as genetic diversity functions in biological systems (as explored in Nassim Taleb’s Antifragile).

This is why we explicitly aim for 70% rather than 100% consent to this framework (discussed in detail later). Universal acceptance would likely require forms of coercion and would eliminate the productive diversity that epistemic certainty provides. The framework seeks to cultivate epistemic humility among those capable of it while recognizing that certainty has its own legitimate place in healthy cultural evolution.

The question is not whether certainty should exist but whether those capable of epistemic humility can create sufficient shared ground to engage productively across differences—even with those who hold certainty. Can the 70% with epistemic humility create conditions where disagreements can be held constructively, where certainty can challenge without dominating, where multiple ways of knowing can coexist productively? That is a question we seek to explore and we offer this framework as a possible guide to help us answer that question.

Assumption 2: The Epistemic-Ontological Distinction

The second foundational assumption involves a critical distinction between epistemic claims (claims about how we know) and ontological claims (claims about the fundamental nature of reality, being, and becoming). This framework explicitly focuses on epistemology while carefully avoiding strong ontological claims—a discipline that proves essential for bridging divides.

What We Mean by Epistemic vs. Ontological

Ontological claims assert something about the fundamental nature of reality itself:

“God exists” (or “God does not exist”)

“Consciousness is nothing but neurons firing” (or “consciousness is fundamental to reality”)

“Only physical matter is real” (or “spiritual realms exist beyond the physical”)

“Free will is an illusion” (or “free will is metaphysically real”)

These are claims about what is—about the ultimate structure and nature of reality, independent of how we come to know about it.

Epistemic claims assert something about how humans come to know and understand reality:

“Prayer is used as a method for understanding divine will in evangelical communities”

“Meditation provides direct first-person access to aspects of consciousness”

“Randomized controlled trials can establish linear cause-effect relationships under bounded conditions”

“Place-based relationship over generations yields reliable knowledge about ecosystems”

These are claims about methods of knowing—about the processes, practices, and approaches humans use to generate understanding.

Why This Distinction Matters

The distinction matters profoundly because ontological disagreements are precisely what this epistemic framework is meant to help hold productively. Consider the challenge raised in critique of this work: if a hardline atheist and an evangelical Christian engage with this framework, what exactly are they agreeing to?

If the framework asked them to agree on ontological claims—whether God exists, whether prayer reaches the divine, whether spiritual experience reveals ultimate truth—it would immediately fail. These are the very disagreements we’re trying to navigate, not resolve by fiat.

Instead, this framework asks them to agree on epistemic claims that can be verified across multiple ways of knowing:

That these methods exist and are used: The claim that evangelical Christians use prayer as a method for understanding God’s will, or that Buddhist practitioners use meditation as a method for understanding consciousness, can be verified through objective observation, through studying patterns across communities, through personal engagement with these practices, and through sustained relationship with practitioners. This is an epistemic claim supported by what might be called “epidemiological” evidence—we can observe, document, and study these incidence and prevalence of these practices occurring within and across cultures and communities.

That different ways of knowing can produce internally valid claims: The framework asks for agreement that when someone uses a rigorous method appropriate to their way of knowing—whether scientific measurement, contemplative practice, systems modeling, or place-based relationship—they can generate claims that are valid within that framework and according to its standards of adjudication. This doesn’t require agreeing these claims are ontologically true, only that they represent genuine knowledge according to the standards of that way of knowing.

That ontological truth claims require robust adjudication pathways: The framework explicitly acknowledges that whether claims are ontologically true—whether they accurately describe reality as it fundamentally is—remains an open question requiring careful processes for adjudicating between competing claims. The framework doesn’t claim to have solved this problem but proposes it as the ultimate aspiration: creating infrastructure for productively adjudicating ontological claims across different ways of knowing.

The Long-Term Ontological Aspiration

To be clear: this framework is not claiming that ontological questions do not matter or cannot be answered. Quite the opposite. The entire purpose of staying carefully epistemic is to eventually enable progress on ontological questions.

The model here is the Bohr-Einstein debates about quantum mechanics. Two brilliant physicists held fundamentally different beliefs about the nature of quantum reality—ontological disagreements about what was fundamentally true. But because they shared an epistemic framework (the scientific method), they could engage in fierce, productive debate that led to subtle, testable predictions. Through their careful work articulating assumptions and developing precise concepts that could be operationalized and tested, they created conditions where their ontological disagreement could eventually be empirically adjudicated (via Bell’s theorem and subsequent experiments).

The question driving this work is:

Could that type of productive disagreement happen across different epistemologies?

Could an atheist and a theist engage like Bohr and Einstein did—fiercely debating ontological questions while using a shared meta-epistemic framework that allows them to identify specific, bounded areas where their different assumptions lead to testable predictions or claims?

This is an extraordinarily ambitious aspiration, and we make no claim to have achieved it with this first prototype. What we offer instead is a starting hypothesis about the infrastructure that might eventually enable such adjudication: a framework that maps the different ways of knowing with sufficient precision that people using different methods can understand each other’s epistemological approaches well enough to identify where their ontological disagreements might be productively tested.

Building on Structuralism and Post-Colonial Critique

This epistemic focus builds on converging insights from multiple intellectual traditions:

From structuralism (particularly Lévi-Strauss): We recognize that humans live embedded in cultures that provide conceptual inheritances—systems of concepts, norms, beliefs, and practices that shape how we understand reality. These structures profoundly influence what we can perceive and how we interpret experience (a point that is reinforced by Neuroscience today, see Episode 4).

From post-colonial critique (particularly Said’s Orientalism): We reject the presumption that Western conceptual frameworks represent “universal structures” through which all other cultures should be understood. The Western canon is one cultural tradition among many, not a neutral or privileged vantage point for adjudicating truth.

From phenomenology and embodied cognition: Unlike radical post-modern positions (such as Derrida’s deconstruction), we do not conclude that there is no truth, no foundation, or that all interpretations are equally valid. Instead, we argue that conceptual knowledge alone cannot fully ground truth claims— ”Natural Laws” and ontological understanding require integration with experiential ways of knowing to establish stable epistemic foundations.

This synthesis suggests that while cultures provide different conceptual frameworks (structuralism), and while no single cultural framework should be presumed universal (post-colonial critique), this doesn’t mean reality is merely socially constructed or that truth is unattainable (against radical relativism). Instead, it means we need frameworks that can integrate both conceptual and experiential ways of knowing across cultural boundaries—precisely what this four-quadrant model attempts to provide.

The Range of Ontological Positions

One reason the epistemic-ontological distinction matters is that tremendous range exists even within categories often treated as monolithic. Consider claims about “God”:

Monotheism: One personal God who created and sustains reality

Deism: God as creator who doesn’t intervene in natural processes

Atheism: No divine being or consciousness exists

Non-theism: Ultimate reality beyond concepts like “existence” or “non-existence”

Pantheism: God and nature/universe are identical

Panentheism: All reality exists within God, but God exceeds reality

Each position makes distinct ontological claims. Yet proponents of different positions might all use contemplative practices, might all engage with objective observations, might all value systems thinking, might all honor place-based relationship. The ontological differences don’t prevent epistemic agreement about valid ways of knowing.

Moreover, sophisticated theological and philosophical work increasingly explores these distinctions with great subtlety (see, for example, Philip Goff’s Why? The Purpose of the Universe, which explores pantheist and panentheist possibilities through rigorous philosophical analysis). This intellectual ferment suggests that maintaining careful epistemic discipline while holding ontological questions open creates space for productive inquiry that prematurely collapsing into ontological claims would foreclose.

Examples of Productive Cross-Epistemic Bridge-Building

Real-world examples demonstrate that epistemic bridge-building across profound ontological differences is possible:

The Dalai Lama’s The Universe in a Single Atom: The Dalai Lama, coming from Tibetan Buddhist tradition with specific ontological commitments, carefully uses Buddhist thinking and contemplative methods to advocate for the complementarity of first-person approaches with third-person objective scientific methods. He neither dismisses science nor abandons Buddhist ontology. Instead, he shows how different epistemologies can mutually inform without requiring ontological agreement.

Paul Mills’ work on science and transcendence: Mills, a rigorous scientist, explores how scientists themselves grapple with transcendent experiences and first-person meditative knowing while maintaining scientific integrity. His work demonstrates how the same person can engage multiple ways of knowing—experiencing transcendence through contemplative practice while studying measurable phenomena through objective scientific methods—without forcing them into false synthesis.

These examples suggest that maintaining epistemic discipline—being clear about what kind of knowledge claim is being made and which methods are appropriate for evaluating it—allows engagement across ontological divides that collapsing everything into a single ontological framework would prevent.

Assumption 3: Epistemic Fit as Guiding Principle

The third foundational assumption introduces a concept we (Steven De La Torre and Eric Hekler) been developing called epistemic fit: the principle that knowledge claims need to be matched to appropriate representations and methods observation and testing. Not all truth claims can or should be adjudicated the same way, and productive disagreement requires clarity about what kind of claim is being made and what epistemological tools are appropriate for assessing it.

The Core Concept

Epistemic fit operates at multiple levels:

Representational fit: Different phenomena require different representational frameworks. Linear causal models fit some phenomena (billiard ball collisions) but not others (ecosystem dynamics, consciousness). Network models capture some patterns (social influence) but obscure others (developmental trajectories). The choice of representational framework shapes what can be perceived and understood.

Methodological fit: Different types of claims require different methods of investigation. A claim about the chemical composition of water demands spectroscopic measurement. A claim about ecosystem resilience demands systems modeling over time . A claim about the subjective experience of meditation demands first-person phenomenological methods. A claim about right relationship with a particular watershed demands sustained place-based participation . Using the wrong method to evaluate a claim generates confusion, not clarity.

Adjudication fit: Different types of knowledge claims require different processes for adjudication (discussed at length below). Attempting to adjudicate one type of claim using another’s methods leads to category errors.

Why Epistemic Fit Matters

Consider what happens when epistemic fit is violated:

Example 1 - Measuring transcendence: A claim about the experience of transcendence during prayer is making a first-person phenomenological claim. Someone who has never meditated or prayed cannot adjudicate this claim through external measurement alone. They can measure physiological correlates—brain activity, heart rate variability—but these measurements cannot capture the subjective quality of the experience itself. Using objective methods to adjudicate personal experiential claims represents a category error, mistaking correlates for the phenomenon itself (the famous “Mary’s Room” thought experiment in philosophy illustrates this).

Example 2 - Prayer’s healing efficacy: A claim about prayer’s efficacy in healing measurable disease outcomes makes an objective empirical claim that can and should be tested with appropriate methods . If someone claims “prayer heals cancer,” they’re making a claim that objective scientific methods can test. If the claim shifts to “prayer provides meaning and peace during illness,” that’s a different type of claim requiring different methods of evaluation. Clarity about epistemic fit reveals these are not competing claims about the same thing but different types of claims requiring different methods.

Example 3 - Climate modeling and Indigenous observation: Systems-focused Water’s climate models make claims about large-scale patterns and future trajectories based on mathematical relationships between variables. Living Air’s place-based Indigenous knowledge makes claims about specific ecosystem changes observed through generations of direct relationship. These are different types of knowledge with different appropriate domains. Water excels at identifying global patterns; Air excels at context-specific understanding and implementation. Neither can substitute for the other. Epistemic fit suggests both are needed, each in its appropriate domain.

Integration: How These Assumptions Work Together

These three assumptions—epistemic humility, the epistemic-ontological distinction, and epistemic fit—function as an integrated whole:

Epistemic humility creates the relational and psychological conditions necessary for engagement. Without it, people cannot genuinely encounter other ways of knowing on their own terms.

The epistemic-ontological distinction clarifies what we’re agreeing to and what remains open for debate. It allows profound ontological disagreements to be held within shared epistemic frameworks.

Epistemic fit provides practical guidance for navigating disagreements by clarifying what types of claims require which methods of evaluation and adjudication.

Together, they establish the “agreements for holding disagreements” (a flip on James Davison Hunter’s phrase as discussed in Episode 1): We agree that multiple ways of knowing exist and have validity (epistemic humility). We agree to focus first on how we know rather than demanding ontological consensus (epistemic-ontological distinction), such that, if epistemic agreement can occur, it creates the conditions for ontological disagreements to be adjudicated. We agree to match claims to appropriate methods of evaluation (epistemic fit).

These agreements don’t resolve all conflicts or guarantee consensus. They create conditions where conflicts can be held productively, where genuine dialogue becomes possible, where people using different ways of knowing can engage constructively rather than talking past each other or demanding that others abandon their methods in favor of one’s own.

The Four Elements Epistemic Framework

At the heart of this project is a framework that recognizes four complementary ways of knowing, each with it’s on range of plausible forms, distinct strengths, limitations, appropriate domains of application, and—critically—different processes for adjudicating truth claims. These quadrants and the overall framework is meant to be a conceptual/methodological representation for organizing understanding and facilitating dialogue. It is not meant to offer ontological claims about how reality is fundamentally structured, though we do hope it is in resonance with other work, including developmental perspectives as well as the metaphysical foundations laid out thus for in this podcast (see Episodes Two, Three, and Four).

The Conceptual Ways of Knowing: Earth and Water (together, the Objective Way)

The Earth and Water quadrants share a common epistemological foundation: both operate through conceptual knowing and employ similar processes for adjudicating truth claims. This shared structure—what I (Eric) have been calling throughout the podcast “The Objective Way”—is what enables trustworthy scientific consensus to emerge and evolve over time.

How Truth Claims Are Adjudicated in Earth and Water

I (Eric) have been developing with scientific colleagues a framework for transforming the scientific enterprise. Central to this is to articulate a set of principles to guide scientific inquiry. Below are two of the six we are developing focused on advancing trustworthy scientific consensus, which we contend involves navigating two fundamental (both-and instead of either-or) polarities:

The Diversity|Resonance Polarity: Drawing on philosopher of science, Boaz Miller’s work, trustworthy scientific consensus requires three characteristics: social diversity (ensuring exploration of diverse hypotheses and perspectives), apparent consilience from diversity of methods—the convergence of evidence (different research methods with different assumptions leading to common conclusions)—and social calibration (structured approaches for adjudicating competing truth claims). While diversity prevents false consensus and mono-method bias (the first two factors), it requires structures to produce consensus statements (third factor) through:

Clearly specifying boundary conditions delineating when, where, and for whom phenomena and competing hypotheses are relevant

Gathering, organizing, and synthesizing the totality of relevant evidence to establish a common base for adjudicating competing hypotheses and truth claims

Employing structured approaches for managing contestation, such as carefully designed experiments that can vet competing hypotheses against one another (like the famous Bell experiment adjudicating between Bohr’s and Einstein’s interpretations of quantum mechanics), extensions of Bayes Theorem to compare hypotheses against evidence and produce probabilistic estimates for each, or the use of mathematical proofs that rule out some possibilities, logically.

The Reproducibility|Autonomy Polarity: Scientific consensus statements are inherently conditional, emerging from well-bounded areas of focus through disciplinary social construction. This conditionality establishes the need for evolution of scientific consensus based on shifts in how humans organize themselves, changes in available relevant evidence, and new understanding from varying approaches to resolving contestations. The polarity recognizes the need to continually balance the tension that emerges between the need to ensure study rigor through replications with supporting individuals and groups in challenging current conventions—recognizing that paradigm shifts (like Einstein’s challenge to Newton) require individuals to explore alternative hypotheses outside current paradigms, often guided initially by experiential knowledge, metaphors, intuitions, and other wisdom outside the realm of current paradigmatic objective knowledge (i.e., that which is part of the right-hand quadrants of the model, labeled here as Earth and Water).

These polarities establish the methodological foundation shared by both Earth and Water quadrants. The key distinction between them lies in what they conceptualize rather than how they adjudicate truth claims.

As a general note, we would argue that the immense power and trustworthiness of insights that emerge from this consensus generation process is an incredible achievement of humanity writ large. Critically, this approach has enabled a range of different disciplines and ways of knowing to develop strategies for adjudicating truth claims toward the goal of consilience, or truth claims that are supported across differing disciplines, methods, and approaches. As described in a sister text only piece, consilience across disciplines and ways of knowing is a critical aspiration that I (Eric) seek to contribute to in this project.

With this robust approach for resolving contestations of truth claims established for both Earth and Water, we now turn to the two elements of the overall “Objective Way” (right-side quadrants).

Earth (Personal-Conceptual): Boundary Work

Overarching Concern: The Earth quadrant represents “boundary work”—the creation, refinement, communication, and manipulation of concepts that occur between humans. This is fundamentally about how we establish and work with conceptual distinctions that allow us to perceive, describe, and share understanding of different aspects of reality.

Perspective: Earth operates from a third-person perspective, enabling objective analysis and measurement of phenomena through concepts that can be shared across observers (and, as described in Episode 4, are also central for humans to experience reality).

Generic Process: The process centers on creating, copying, communicating and collaborating around conceptual objects (concepts, words, categories that stand for aspects of reality), establishing boundaries that distinguish one concept from another, and, as needed to enable effective communication and collaboration in relation to a concept, developing increasingly precise definitions and protocols for enacting the concepts (e.g., measurement strategies, procedures, practices, etc) that extend our collective capacity to perceive and communicate about reality (including physical, social, and spiritual facets of reality).

Range of Forms: The forms this epistemic quadrant takes vary widely based on what communities focus their attention upon and the degree of precision they require for effective communication. All human cultures leverage this quadrant since all use language and representational systems to communicate. The distinctions between cultures and communities emerge from what they direct this concept-creation capacity toward and how deeply they engage in creating ever more refined and precise usage of those concepts.

Example Forms and Their Dimensional Extremes: On one end, we find bounded concepts exemplified by objective measurements—the highly constrained, precisely defined concepts central to reductive physical sciences. Think of measurements like temperature in Kelvin, molecular weights, or the precisely bounded categories of elements in the periodic table. Here, earth (lowercase) represents the physical, bounded nature of concepts—like rocks and soil, these are discrete, measurable, clearly delineated. These reductive approaches function by establishing boundary objects that can be translated into objective measurements through procedures that extend human perception or can be stored and manipulated. On the other end, we find boundless concepts that reach toward ultimate wholeness and oneness—concepts like God, transcendence, eternal witness consciousness, Turiyarita, Samadhi, unconditional love, infinite, zero, universe, cosmos, and Mother Earth (uppercase). These concepts, while still linguistic tools requiring boundaries for communication, point toward that which encompasses everything, the unbounded ground of being itself and, thus, by definition, recognize that the concepts are only partial representations of that which is being sought to be represented.

The Double Meaning of Earth/earth: We call this quadrant “Earth” to honor both dimensions of conceptual work and to acknowledge the common cross-cultural pattern of recognizing four elements. The double meaning is intentional: earth (lowercase) signifies the bounded, material nature of precise concepts—the rocks and soil that can be measured, categorized, and manipulated. Earth (uppercase) represents our planetary mother who birthed and holds all of us—the boundless, encompassing whole that transcends any single measurement or category. This duality reflects the full range of conceptual work, from the most reductive analysis to the most expansive synthesis of oneness.

Application Across Cultures: Any time language and other representational systems are being used, this quadrant’s gifts are being drawn upon. Thus, in all human cultures, given all use some type of language and concepts, there is use of this quadrant’s gifts. Critically, all concepts, given their orientation as language tools, are definitionally cultivated in relation between humans as they are meant to help humans communicate. Thus, they emerge from personal and relational experiences (left hand quadrants) in a both-and type of dynamic (this was all implied in Episode 4).

With this general pattern articulated, Earth, at its most basic level, is the creation of concepts and representations of some facet of reality (including both physical and social realities, see Episode 4, and, aligned with the other quadrants, also spiritual reality concepts, such as the boundless concepts shared earlier). This capacity to create, communicate, copy, and collaborate around concepts is used and leveraged across all cultures, and this logic is in resonance with what we know from contemporary neuroscience (see Episode 4). Given the sub-dimensionality of both different focus and also the degree of precision of the concept, the array of possible concepts is likely infinite.

To give but one example, reductive physical scientific methods (e.g., physics, chemistry, biology), with their focus on understanding material aspects of reality, coupled with their strong commitment to ever finer perceptual capacity regarding elemental concepts (e.g., rocks to molecules to atoms to quarks), represent a valuable and important example of communities of people (in this instance, humans committed to and engaging as part of a relational network of a discipline) working together. Thus, this capacity, within these disciplinary communities based on their focal concern and their commitment toward precision, has resulted in: (a) creating conceptual objects (concepts, words, categories that stand for aspects of reality); (b) isolating specific phenomena by drawing boundaries around them; and (c) developing replicable procedures for measurement that others can repeat using instruments that capture observable, quantifiable aspects of reality. This is commonly labeled reductive scientific methods and, hear, could be thought of as a reductive earth activity.

Strengths: At its most basic, this area involves the exploration of boundaries, both in their creation and destruction, that manifest in the form of concepts, particularly words and other ideas. Each community of people, given their focal area and level of interest in precision regarding the capacity to communicate, develops varying repertoires of concepts to communicate and understand their focal area of concern.

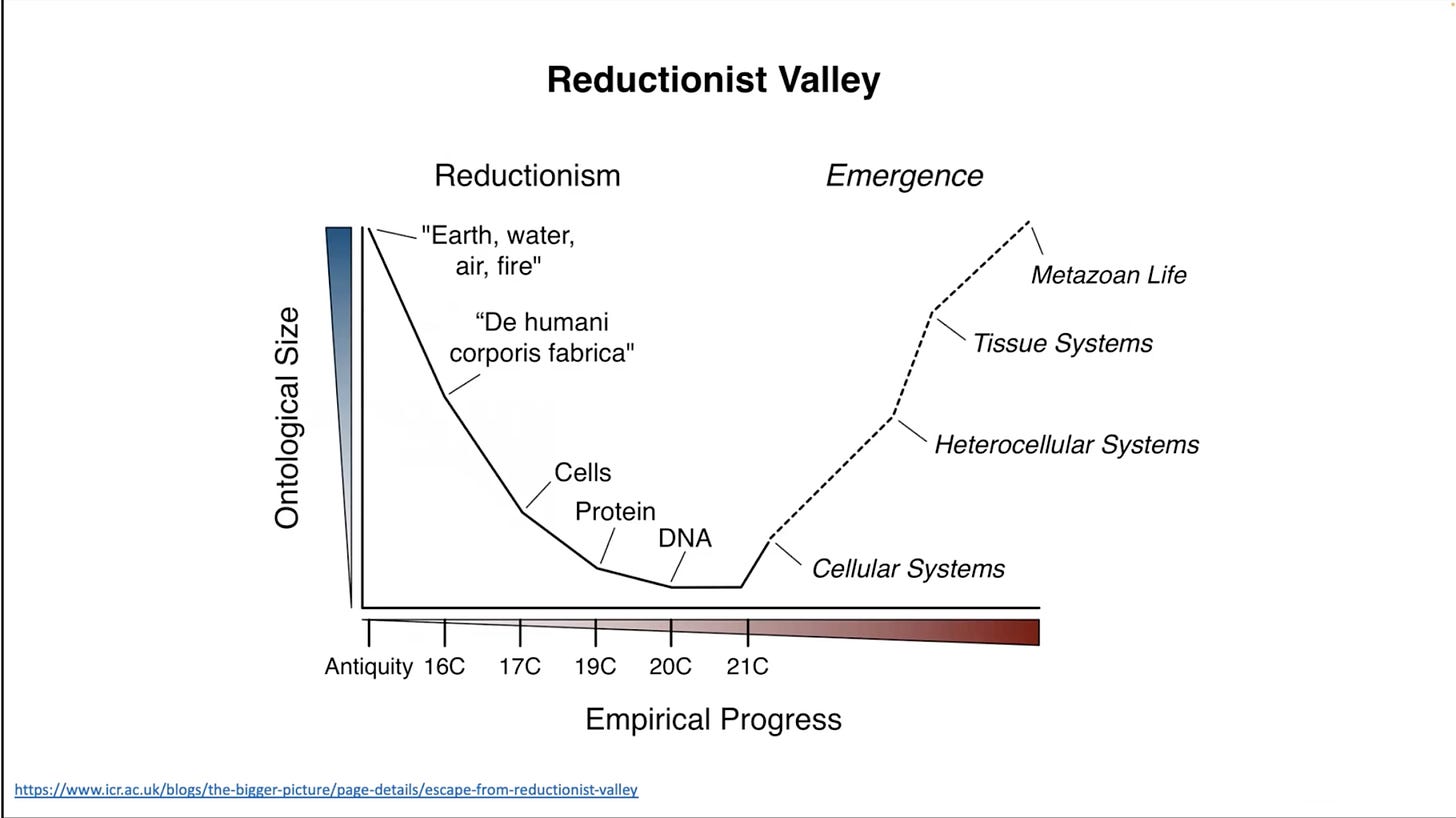

For example, reductive methods function by establishing boundary objects (concepts) that can be translated into objective measurements (procedures that extend human perception or can be stored and manipulated). In addition, there is often a strong drive toward seeking the most “fundamental” element (e.g., see this image visualizing the “reductionist valley” within biological sciences, which we drew from here (note the “emergence” side of the “valley” is what we are labeling in this framework the “Water” quadrant, representing systems science; thus, this “valley” is one possible visualization of the right quadrants with the reductionism side on the upper right and the emergence side on the lower right):

Image above from here: https://tape-lab.com/blog/2016/8/25/escape-from-reductionist-valley

We might label this reductive approach classically used in physics and otherwise as Newtonian thinking (see this episode discussion with Geoscientist Marcia Bjornerud for more on this) to signify science seeking universal and timeless truths. Critically, there is a strong focus on seeking to articulate objective essences, meaning the smallest fundamental elements that, if understood, the logic goes, could then be systematically reconstructed to understand all other elements that are built upon this foundational essence (this is likely a core drive behind string theory theorists, and is discussed in the final chapters of Timothy Palmer’s book, The Primacy of Doubt, whereby he makes the case that reductive essentialism may be a dead end for physics). This, particularly when coupled with the systems thinking tools and approaches (thus, what has been labeled “The Objective Way” in this podcast and is now more formally represented and described in the right hand quadrants), has enabled the veritable explosion in engineering and technological capacities that we experience today.

Overall, Earth ways of knowing can produce trustworthy scientific consensus statements rigorously vetted and independently verified within the boundaries of the focus for a given discipline/group working together. The great gift of this, within a community/discipline, is ever-increasing perceptual precision around some facet of reality (going down the reductive valley as visualized above). The added gift, if robust strategies can be created to support effective translation between communities (which is a key focus of this work), is that, across humanity and human history, we have a vast array of concepts we could feasibly draw upon to help us navigate and understand reality.

Limitations: By necessity, concepts work with boundaries and thus always produce “maps of territory” and are not the territory itself. When used in isolation, they struggle with emergent properties, experiential knowledge, and phenomena resisting isolation. The very act of drawing boundaries excludes context and relationship on one end. If not careful, they also can drive one toward seeking ever-smaller elements, thus driving one to the proverbial “missing the forest for the trees” phenomenon. On the other end related to the erasure of boundaries, this can result in flattening and washing out potentially valuable and meaningful variation and diversity that the boundaries enable perception of, or the flip side (missing the trees for the forest).

Reliable sources: Expert consensus from a community/discipline in relation to their focal area of concern, peer-reviewed, replicated objective truth claims that are built upon the reliability and trustworthiness of the community/discipline’s capacities.

Gift offered: Precise concepts representing bounded aspects of reality that can be leveraged and replicated by others. From reductive methods (particularly when linked with systems science methods from Water), this has enabled the production of technologies and physical reality claims primarily (for more on physical vs. social reality, see Episode 4).

Boundaries for Truth Claims: Earth, particularly the use of it that leverages reductive approaches to concept creation, is best suited for making truth claims about measurable, bounded phenomena replicable across independent observers, and has been particularly strong around physical reality phenomena (with the possibility of extending to social reality phenomena, a key area of my own scientific research—see my Google Scholar page for papers in this domain, though this extends beyond the scope of this introduction). Reductive Earth methods excel at answering “what is” questions about physical reality phenomena—the melting point of ice, the distance to the moon, the chemical composition of water. However, reductive Earth reaches its limits when addressing meaning, purpose, subjective experience, values (”what should be”), or emergent wholes resisting isolation and reduction. Reductive Earth can describe the neurochemistry of meditation but cannot adjudicate whether the oneness experience is “real” or meaningful. It can measure prayer’s physiological effects but cannot determine whether prayer reaches the divine. When reductive Earth makes claims beyond its boundaries—such as “consciousness is nothing but neurons firing” or “love is merely oxytocin”—it engages in reductionist overreach, mistaking the map (measurements of correlates) for the territory (lived experience and meaning). This point is explored in the famous “Mary’s Room” thought experiment in philosophy.

And, on the flip side of this, traditions that focus on boundless concepts (God, unconditional love, Christ Consciousness, emptiness, etc.) offer the concepts that enable people with appropriate realized wisdom to be able to communicate about these experiences to those who have not experienced this. This enables the creation of instructions on practices to try as well as pointing-out instructions that can guide another person who is interested in experiential understanding of that which these boundless concepts point toward. On this front though, these boundless claims could result in overreach when subtleties that do come into perception actually do matter when focusing on some facet of reality. Thus, just as there is a risk of overreach of reductive Earth approaches, there is a risk of overreach of what might be labeled here transcendent Earth approaches that may artificially wash out and diminish meaningful variation and distinctions that are only observable to a person with the aid of certain boundaries afforded by the use of concepts.

Water (Relational-Conceptual): Connection Work

Overarching Concern: The Water quadrant represents, at its most fundamental level, a focus on exploring and creating connections between concepts—hence the notion of “connection work.” This is about understanding how concepts relate to one another, how they interact dynamically over time, and how patterns emerge from these relationships.

Perspective: Water operates from a fourth-person perspective, enabling synthesis across multiple viewpoints and the modeling of complex relational dynamics that transcend any single observer’s vantage point.

Generic Process: The process centers on connecting concepts to reveal patterns, relationships, and emergent properties. This involves creating narratives, models, and simulations that capture how elements interact and influence each other over time—from simple causal chains to complex computational models of interconnected systems. The work is fundamentally about synthesis—putting concepts together to understand wholes that are greater than the sum of their parts.

Range of Forms: Just as with the Earth quadrant, Water ways of knowing are utilized across all cultures and communities that employ language and storytelling as a way of structuring connections between words and concepts. Different communities orient toward different foci and require different levels of precision for understanding connections between concepts, based on their communicative needs, areas of concern, and the broader contexts the live within and the corresponding pressures that emerge for individuals and communities to adapt to.

Example Forms and Their Dimensional Extremes: On one end, we find mathematical models—acontextual, abstract representations that aim for universal applicability across contexts. These are exemplified by systems science approaches that leverage concepts and objective measures from reductive Earth methods but focus on relationships, patterns, and emergence rather than isolated parts. Think of differential equations describing population dynamics, network models of information flow, or computational simulations of climate systems. Here, water (lowercase) represents the universal flow—the mathematical relationships that could apply anywhere, disconnected from specific place or time, like the molecular structure of H₂O that remains constant whether in a puddle or an ocean. On the other end, we find “right stories”—deeply context-bound narratives that are explicitly tied to particular people, places, and times. These are exemplified by Indigenous storytelling practices that maintain relationship with specific lands and living communities (e.g., see Tyson Yunkaporta’s book, Right Story, Wrong Story). Here, Water (uppercase) represents the specific bodies of water that enable life in particular places—this watershed, this river, this ocean—irreducibly bound to the communities and ecosystems they sustain.

The Double Meaning of Water/water: We call this quadrant “Water” to honor both dimensions of connection work. The double meaning is intentional: water (lowercase) signifies the universal, acontextual nature of abstract models—the flow of H₂O molecules following physical laws regardless of location, the mathematical relationships that hold anywhere and anytime. Water (uppercase) represents the specific, life-giving bodies of water that sustain particular communities and ecosystems—the rivers, lakes, and oceans that are irreducibly context-bound, whose stories are inseparable from the land and life they nourish. This duality reflects water’s nature as both universal solvent and particular place-maker, both abstract connection and embodied relationship.

Application Across Cultures: Just as with Earth ways, Water ways of knowing are utilized across all cultures and ways of knowing that employ language and storytelling. The use of narrative to connect concepts, to explain how things relate and change over time, is universal to human meaning-making. What varies is the focus of attention, the degree of abstraction pursued, and the commitment to either acontextual universality or context-bound particularity.

For example, in systems science, there is a strong focus on leveraging the range of concepts that have been produced across the physical and social sciences and finding ways to create robust system models, with ever-greater precision through mathematics, modeling, and simulations, for creating understanding of—and, by extension, use of—these connections. This is described well in the area of systems science (for a wonderful introductory text about this, please see Mobus and Kalton’s Principles of Systems Science and, for a historical review, consider James Gleick’s classic: Chaos: Making a New Science). This could be thought of as Systems-focused Water work. Systems-focused Water represents ways of knowing that leverage all of the concepts and corresponding objective measures articulated via reductive Earth approaches but, critically, focus on relationships, patterns, and emergence rather than isolated parts.

The use of “Water” as a fundamental element provides visual analogy both in a reductive sense—water (lowercase) flows in and around earth in constant exchange, fostering relationships, patterns, and emergence—and in a holistic sense—Water (uppercase) as an indicator for all the oceans and waters across the planet that enable life to emerge in specific, context-bound ways.

We might label Systems-focused Water as Darwinian thinking (see this episode discussion with Geoscientist Marcia Bjornerud for more on this) to signify science that acknowledges constant change across space and time. This way of knowing creates narratives, models, and simulations capturing how elements interact and influence each other over time, from simple causal chains to complex computational models of interconnected systems. For example, consider the ways in which observations of galaxies are made and then simulation models are run that make varying assumptions about the presence or absence of black holes at the center of galaxies. This work is used to illustrate that the observed patterns of galaxies can only be replicated in simulation models when the black holes are present, thus providing simulated evidence of their existence (which is corroborated by consilient evidence gathered from observations made in relation to the movement of stars near the center of our own Milky Way Galaxy).

Critically though, there are other Water ways, such as Indigenous practices of storytelling that are explicitly place-based and relational between living beings (e.g., see Yunkaporta’s book, Right Story, Wrong Story). The process of connecting concepts is similar, but the focus, context, and required precision for understanding connections shifts. These “right stories” are inseparable from the particular people, place, and time in which they emerge and to which they remain accountable.

Strengths: Water ways of knowing reveal patterns invisible to Earth ways of knowing, show how components interact to produce emergent phenomena, and enable prediction through modeling dynamic relationships. Particularly for Systems-focused Water, it bridges between reductive science and holistic understanding. Another key strength of methods used in this quadrant, including both storytelling and more refined forms like mathematics and systems science methods, is that they foster the emergence of new possibilities, ideas, and insights that might not be immediately obvious based on pure observation. For example, consider the famous Dirac equation formulated by Paul Dirac, which, as Dirac himself said, was smarter than he was, in that it pointed to the possibility of something he had never dreamed of: anti-matter.

Limitations: Models (e.g., stories, mathematical equations, computational models) connecting concepts are always simplifications; the map is not the territory. Most critically, all types of systems and narratives can become so abstract that they become untethered from reality. This can occur with simple stories, narratives, and explanations that emerge from any culture, including, at the extreme, rich and complex systems models. Thus, the key risk of storytelling and simulations is the creation of social reality structures, narratives, and beliefs that are logically coherent systems internal to themselves but fundamentally detached from reality. This has been called both simulacra and hyperrealities. At their core, they rely on concepts rather than direct experience to be tethered to reality, thus creating their great vulnerability.

Reliable sources: Validated predictive models that have been carefully compared with robust measurements of reality, simulation results, pattern analysis.

Focus: Relationships, connections, emergence.

Gift offered: Understanding and emergence through representing relationships and tuning between conceptual elements (both concepts and measures).

Boundaries for Truth Claims: Water can build robust truth claims about patterns, relationships, and dynamics between concepts—how systems behave, what feedback loops emerge, and how components interact over time. However, Water’s truth claims are contingent upon the quality of the evidentiary inputs (i.e., the concepts) upon which they are based. If there is either no tethering to experiential knowledge (e.g., what might be labeled “wrong story” in that the story becomes untethered to the people, place, and time when it was told, as described in Tyson Yunkaporta’s book, Right Story, Wrong Story) or if the foundational objective measures from reductive Earth methods are poorly defined or not well connected to actual reality, then the results and insights gleaned from the stories are less likely to be trustworthy. In addition, if different objects/concepts/observations from different people or communities are utilizing different ontological assumptions or created by different traditions with incompatible boundaries, systems models may appear coherent while actually combining incommensurable elements. Taken together, this is the classic “garbage in, garbage out” problem in mathematics and systems science: Water has no inherent way to assess the quality or compatibility of its conceptual inputs (though humans can feasibly integrate corrections, but that is the critical element of incorporating humans’ “tacit knowledge“ into the system).

This issue gets further complicated as different communities may seek to communicate and create shared understanding. Different communities may use the same word (e.g., “health,” “freedom,” “progress”) with fundamentally different meanings, and systems models combining these without careful ontological work (in both the philosophical and information science sense, but more so the information science sense of seeking to ensure that people can communicate via having the same shared meaning for a word) will produce coherent-seeming but misleading results. Put more simply, Water excels at revealing how concepts relate if concepts accurately represent reality, but cannot independently verify whether they do—that adjudication requires the other ways of knowing.

The Experiential Ways of Knowing: Fire and Air (Spirit’s Way and Nature’s Way)

The Fire and Air quadrants share a foundation in experiential knowing—direct, embodied understanding that cannot be fully captured through conceptual representation, while simultaneously supported by concepts. However, the processes for adjudicating truth claims in these quadrants, at least to the best of our knowledge (and we would truly welcome being corrected!), are less formally codified than in the conceptual quadrants described above and thus remain open areas of inquiry for future work in this Negotiating Reality project. (If anyone reading this has strong knowledge in these areas, we would truly welcome dialogue and invite you to join me (Eric) on a negotiation episode for the podcast.)

Fire (Personal-Experiential): Spirit’s Way

Overarching Concern: The Fire quadrant, at its most fundamental level, represents knowing through personal, direct experience. This is about what can only be known through first-person engagement with reality—the embodied, lived understanding that cannot be fully captured through conceptual representation alone, though it is simultaneously supported by concepts that help point toward and communicate about these experiences (see Episode 4).

Perspective: Fire operates from a first-person perspective, grounding all knowing in the irreducible reality of direct personal experience—what I sense, meditate upon, and come to understand through my own engagement with reality.

Generic Process: The process centers on sensing, meditating upon, and refining one’s capacity to attend to and discern direct experience. This involves disciplined cultivation of awareness and presence, often through sustained practice over time, developing the ability to perceive subtle dimensions of reality that cannot be accessed through conceptual mediation alone.

Range of Forms: Just as with the Earth and Water quadrants, Fire is utilized across all communities, cultures, and traditions. All persons develop knowledge through personal experience. What varies is the focus of attention—what facets of reality persons direct their experiential awareness toward—and the degree of refinement and precision they cultivate in their capacity to perceive and discern subtle dimensions of experience.

Example Forms and Their Dimensional Extremes: On one end, we find tacit knowledge—the concrete, embodied know-how developed through repeated practice and engagement with specific tasks or domains. This is the scientist perfecting their craft in being able to effectively use an assay to measure a phenomenon, the musician’s fingers knowing where to go without conscious thought, the athlete’s body understanding how to move. As described in Michael Polanyi’s Personal Knowledge, this tacit knowing forms the experiential foundation upon which all conceptual knowledge ultimately rests. Here, fire (lowercase) represents the embodied, experiential knowledge gained through living—the heat of engagement with material reality, the concrete practice that builds competence and skill. On the other end, we find revelation—direct experiential knowing of spiritual dimensions of reality accessed through meditation, prayer, and other consciousness-based practices central to contemplative and mystical traditions. This is the direct encounter with transcendent dimensions of reality—experiences of oneness, unconditional love, eternal witness consciousness, or what various traditions call God, Source, Buddha-nature, or the Absolute. Here, Fire (uppercase) represents guidance from Source—the eternal witnessing consciousness and unconditional love that illuminates all experience, the sacred fire that has inspired humanity’s spiritual wisdom traditions across cultures and throughout history.

The Double Meaning of Fire/fire: We call this quadrant “Fire” to honor both dimensions of personal experiential knowing. The double meaning is intentional: fire (lowercase) signifies the concrete, embodied heat of living—the tacit knowledge built through engagement, the experiential capacity to perform tasks like scientific activities, music, or sports, the muscle memory and practical wisdom that comes from doing. Fire (uppercase) represents the sacred flame—guidance from Source, the eternal witnessing consciousness and unconditional love that spiritual practitioners across traditions have encountered through disciplined contemplative practice. This duality reflects fire’s nature as both the immediate heat of embodied engagement and the transcendent light of spiritual illumination.

Application Across Cultures: Fire, in particular, is being developed collaboratively with Kabir Kadre, President of the non-profit organization Open Field Awakening and others in the Open Field Awakening group. Kabir (who is a co-author of this piece) is a long-term member and practitioner within the Integral community with a strong personal and spiritual practice aligned with this quadrant. Indeed, much of what is written below for this quadrant emerged from discussions within the container of Open Field Awakening, such as dialogues between Kabir, Richard Flyer (described below), and myself.

Strengths: For persons focusing on more explicitly bounded facets of reality (e.g., the sorts of areas of inquiry that occur within physical and, to some extent, social sciences), this personal experiential insight, particularly when working in healthy resonance with all the ways of knowing, becomes a powerful pathway for the creation of objective measurement strategies in the form of procedures that can be repeated precisely by other scientists. Thus, it provides the foundational tethering to reality that feeds and enables the Objective Way approach to adjudicating truth claims about phenomena that can fit into this structure.

For persons focused on more explicitly boundless facets of reality, the meditative and contemplative refinements to this way of knowing enable accessing dimensions of reality unavailable to external measurement. It can enable personal experiences about the nature of consciousness itself, enable transformation of the knower, and provide direct insight into meaning, purpose, and value. It offers wisdom about how to live well, what truly matters, and how to respond to suffering.

Limitations: First-person experience cannot be directly verified by others, save unless that tacit knowledge is translated into a replicable procedure mediated by all of the conceptual work in the right-hand quadrants. Particularly for Contemplative Fire orientations, without discipline, discernment, and often a teacher, contemplative knowing can slide into delusion or wishful thinking. It is deeply susceptible to “false prophets” who claim to be enlightened teachers but are not. It requires years of practice to develop reliability. Different traditions sometimes make incompatible claims, and there is no simple way to adjudicate between them using meditative methods alone.

Reliable sources: On one end, deeply disciplined individuals capable of abduction—the translation of experiential understanding of a phenomenon into a concept that can be proceduralized; on the other end, God, Realized teachers, transcendent experience, convergent wisdom across traditions.

Gift offered: Awareness, presence, and direct experiential wisdom (bliss).

How Truth Claims Are Adjudicated in Contemplative Fire: Based on initial explorations, particularly with Richard Flyer, we offer several proposed principles for adjudicating truth claims in contemplative Fire (as the more tacit knowledge Fire approaches ultimately get adjudicated via the Objective Way process described above). The rest are hypotheses to be tested in dialogue with others:

Radical Humility Regarding Translation: While first-person revelation is definitionally true as experiential reality for the person who experiences it, the translation of that revelation into words, concepts, and explanatory frameworks must be held with profound humility. In a conversation with Eric, Kabir, and Richard, we explored the paradox of revelation—that the universal is always entangled with the particular—must be navigated. While the experiential core can be absolute, its conceptual expression is always conditional on the person’s history, lineage, and culture.

Relationship as Primary Adjudication Structure: Truth claims in Fire are validated not through impersonal procedures but through sustained relationship over time. As Richard articulated: “I’ve come to trust that the more intimate and luminous a truth is, the more gently it must be carried across difference.” This points to the possibility that adjudication happens through:

Being in sustained relationship with realized teachers whose lives demonstrate the wisdom they profess

Participating in communities of practice where claims can be tested through one’s own direct experience

Observing whether teachings lead to genuine transformation (reduced suffering, increased compassion, deeper peace) across multiple practitioners over time

Maintaining accountability to lineages and traditions that have refined practices over generations

Frequency-Based Reasoning About Applicability: Rather than claiming universal applicability, Fire’s truth claims can be understood through what might be called “population-based” reasoning—acknowledging that different spiritual paths and revelatory truths resonate with different populations based on culture, context, and lived experience. This allows honoring the absolute truth of one’s own and one’s tradition’s expression of revelation while recognizing it may not be experienced in a similar fashion among other spiritual traditions. This possibility is beautifully expressed in Islam via the notion of the 99 faces of God, as described in A. Helwa’s Secrets of Divine Love. Overall, this point is critical as it enables a pathway for honoring the potential universal commonalities of revelation across cultures and traditions while also recognizing that the form these personalized revelations manifest in each person or community may, on the surface, look quite different. (As is commonly shared in Christian communities, The Lord works in mysterious ways; O Magnum Mysterium).

Drawing Supportively from Objective Way: Fire can draw on Earth and Water’s methods to support (but not replace) its truth claims—using frequency estimates of population alignment, empirical observation of practice outcomes, historical documentation of convergent testimony across traditions. For example, one could imagine the use of Earth approaches to seek to describe exactly when, where, and for whom various revelatory experiences manifest in different communities and cultures, and to then engage in epidemiological types of studies to determine the incidence and prevalence of those types of experiences in communities and to see if there are correlations of praxis and lineages that produce or do not produce said revelations. Critically here, the core adjudication must remain experiential and relational rather than purely conceptual, as the core tethering. Thus, this type of approach must be done carefully and in a container of good relationship, humility, curiosity, and compassion to ensure the Objective Way tools are calibrated such that they truly honor the experiential ways of knowing.

Convergent Testimony Across Traditions: Drawing upon Objective Way tools, if done in careful honoring and understanding of the inherent experiential nature of the phenomena itself, then it might open up interesting pathways for supporting different spiritual traditions to see patterns and resonance across spiritual traditions. Specifically, when multiple independent spiritual traditions, using different practices and arising from different cultures, report similar experiential discoveries (e.g., experiences of oneness, unconditional love, transcendent peace), this represents a form of consilience—different procedures aligning on a common conclusion. The more different spiritual traditions align on common conclusions, the more it supports the claim that these phenomena may be reliable features of consciousness accessible through disciplined practice. That said, in line with the inherent conditional nature of any verbal claims (and thus, conceptual/representational claims), these claims cannot be viewed as absolute and instead are conditional and open for revision, just as is the case with any claims that are reliant on the Objective Way approaches (Earth and Water).

Open Questions for Exploration: The Contemplative Fire quadrant invites ongoing inquiry into several critical areas. How do we distinguish mature from immature spiritual claims? How do different traditions’ incompatible metaphysical claims (theism, panentheism, non-theism, atheism) relate to potentially shared experiential cores? Can “experiential sensors”—collections of disciplined practitioners using shared methods—begin building consensus analogous to scientific consensus? What role should criteria like “reduced suffering” and “increased compassion” play in validating spiritual claims? How do we identify and address “false prophets” and spiritual harm? How also do we separate the influence of spiritual praxis from the religious institutions meant to nurture said spiritual praxes? These questions require the kind of sustained, careful dialogue that we hope to facilitate in the future in the Negotiating Reality space.

Boundaries for Truth Claims: Contemplative Fire can make strong truth claims about first-person phenomenological reality—what is directly experienced through disciplined meditative and contemplative practice. Claims like “I experience peace in meditation,” “I feel divine love,” or “I know oneness through sustained practice” are legitimate truth claims within Fire’s domain and do not require external verification. Instead, they are true for that person and their personal experience and, for them, this truth can be unconditional and universal. While that might be true and a universal type of personal experience, it is up to each person to do the work of discovering this truth or not, on their own, hence the critical limit to this way of knowing.

Contemplative Fire reaches its limits when making empirical claims that move into concepts being transferred and thus move into Earth and Water domains—claims such as the age of the universe, the efficacy of prayer for healing disease, or factual assertions about historical events all move into the realm of that which can be tested via Objective Way (Earth/Water) approaches. When Fire makes claims about that which can be translated into an objective, measurable tool, Earth and Water’s methods must be incorporated to foster adjudication of these claims, particularly an exploration of when, where, and for whom these claims may or may not be valid. Critically though, Earth/Water claims cannot overstep into claims that are beyond their areas (see above).